Great savings governments will reject

The main purpose of commissions of audit is to provide new governments with flint-hearted suggestions they can ignore, and thus make a show of being nice while doing what they were going to do anyway.

In that respect Tony Shepherd’s commission has done its job, parading weeping pensioners and mothers, distraught patients, incensed scientists and soldiers and crumpled public servants about to lose their jobs whom the Prime Minister can comfort with a “deficit levy” instead.

There there: we won’t do all that nasty stuff Mr Shepherd wants. We’ll tax the rich instead.

With that in mind, some of the recommendations issued today must be taken with a grain or two of salt.

Many are there specifically to be rejected, as happened with most of the ones in the 1996 audit commissioned by John Howard, not to mention the Henry Tax Review commissioned by Kevin Rudd.

The real value in today’s report is not so much in the recommendations (the boffins in Treasury and the Treasurer’s office all know what to do already) as in the clear, public picture it paints of Australia’s hopeless fiscal mess, the clarity with which it describes the duplication between the Commonwealth and the states and its pitiless examination of the efficiency and purpose of the public service.

There are two key pillars of this Commission of Audit’s work: better targeting of welfare through means test reforms, and a shake-up of the way in which government operates, including a big transfer of money and responsibility from the Commonwealth to the states.

And although much of the focus in the next few days will be on the recommendations about pensions and other welfare benefits, the real value of the report is in the structural reforms proposed to the way government operates in this country.

It is a more specific and therefore more useful report than the one produced in 1996 for the Howard government, although many of the recommendations are simply a repeat of what the 1996 Commission headed by Professor Bob Officer recommended.

Eighteen years on there may be more chance of these reforms being taken up, but that won’t be in this month’s federal budget -- more time will be needed.

The Commission of Audit was asked to recommend expenditure savings sufficient to achieve a surplus equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP in 10 years' time.

According to Treasury’s “medium term” forecasts (from the Mid Year Fiscal and Economic Outlook five months ago), the underlying cash deficit in 2023-24 will be 0.5 per cent of GDP.

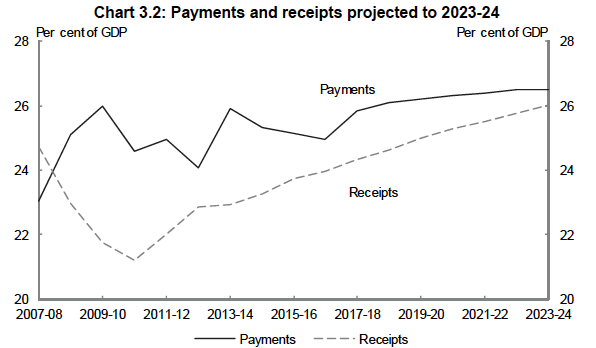

Here is the graph of payments and receipts out to 2023-24 from last year’s MYEFO:

Naturally the forecasts of the Commission of Audit are worse (no self-respecting commission of audit can agree with Treasury).

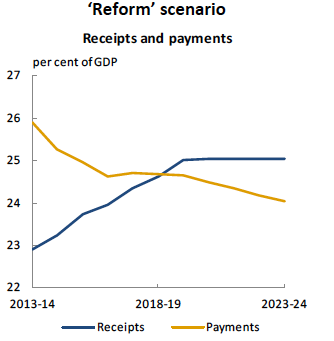

The projected underlying cash deficit under its “Business As Usual” scenario is about 1.5 per cent of GDP. Here is its graph of payments and receipts:

The obvious difference between these two graphs is that the Commission of Audit’s receipts line goes flat after 2020.

The reason is bracket creep, or fiscal drag, which the commission has decided is unsustainable. It would mean, according to the report, that the average wage earner’s marginal tax rate would rise from 32.5 to 37 per cent over ten years, and for someone on the minimum wage from 19 to 32.5 per cent.

Treasury apparently thinks that’s fine.

Without bracket creep, and with tax receipts staying below 24 per cent of GDP, the deficit simply keeps growing.

So here is the commission’s 'Reform Scenario', which gets the budget to a surplus of 1 per cent of GDP in 2023-24, as required by the terms of reference:

On the question of Commonwealth State financial relations, the Shepherd commission, like the Officer one 18 years ago, wants to start unwinding 40 years of centralisation that started with Gough Whitlam.

It suggests (but doesn’t recommend) that the Commonwealth could reduce the 32.5 per cent personal income tax rate to 22.5 per cent and hand over the cash difference (about $25 billion) to the states, while reducing tied grants by the same amount.

This would allow the Commonwealth to slim down (but not abolish) the Departments of Education and Health, since those are functions for which the states have responsibility.