Godzilla is good for you?

Fans of Japanese schlock fiction will be pleased to know that that old mega-favourite Godzilla is returning in 2014, to stomp on simulated cities in a cinema near you. And of course, he’s bigger and better: the original Japanese movie had him at about 50-100 metres and weighing 20-60,000 tons; I’d guess he was about twice that size in the 1998 US remake; and by the looks of the trailer for the 2014 movie, he’s now a couple of kilometres tall and probably weighs in the millions.

That’s good: when you want thrills and spills in a virtual world, then as it is with sport (according to Australian comedic legends Roy and HG) too much lizard is barely enough. The bigger he gets, the more he can destroy, which makes for great visual effects (if not great cinema).

But in the real world? The biggest dinosaur known came in at about 40 metres long, weighed “only” about 80 tonnes, and had an estimated maximum speed of eight kilometres an hour. In the real world, size imposes restriction on movement, and big can be just too big. So a real-world Godzilla is an impossibility.

Cinema -- especially CGI-enhanced cinema -- can overcome the limits of evolution, and therein lie the thrills and spills of Godzilla: the bigger he is, the more terrifying. Godzilla is scary purely because of his scale: a 100 metre Godzilla is scary; the 1 metre iguana species from which he supposedly evolves is merely cute. In Godzilla, there is a positive relationship between size and destructive capacity.

Maybe Bank of England governor Mark Carney should attend the UK premiere, because he clearly needs to learn this lesson and apply it to his own bailiwick. If he can’t learn it from economics, then maybe he can learn it from the movies by analogy: finance is dangerous in part because, like Godzilla, it is too big.

Instead, as Howard Davies -- himself an ex-deputy governor of the Bank of England -- observed in a recent Project Syndicate column, Carney seems almost to celebrate the prospect that the UK’s financial sector -- now with assets four times the size of its economy -- might grow to nine times the size of GDP if current trends continue.

“Bank of England Governor Mark Carney surprised his audience at a conference late last year by speculating that banking assets in London could grow to more than nine times Britain’s GDP by 2050… the estimate was deeply unsettling to many. Hosting a huge financial center, with outsize domestic banks, can be costly to taxpayers. In Iceland and Ireland, banks outgrew their governments’ ability to support them when needed. The result was disastrous,” Davies said.

In a speech marking the 125th anniversary of The Financial Times, Carney noted that when the paper was founded, “the assets of UK banks amounted to around 40 per cent of GDP. By the end of last year, that ratio had risen tenfold.” He then noted that if the UK maintains its share of global finance, and “financial deepening in foreign economies increases in line with historical norms”, then “by 2050, UK banks’ assets could exceed nine times GDP, and that is to say nothing of the potentially rapid growth of foreign banking and shadow banking based in London.”

From 40 per cent to 400 per cent of GDP in 125 years, and then from 400 per cent to 900 per cent in another 35: even the Godzilla franchise would be impressed with that rate of growth. And Carney seems to relish the prospect. Though he notes that “some would react to this prospect with horror. They would prefer that the UK financial services industry be slimmed down if not shut down”, he next stated that “in the aftermath of the crisis, such sentiments have gone largely unchallenged”. And he proceeds to challenge them.

After stating that “if organised properly, a vibrant financial sector brings substantial benefits”, he denied any responsibility in determining how big the financial sector should be -- either absolutely or relative to the economy:

“It is not for the Bank of England to decide how big the financial sector should be. Our job is to ensure that it is safe,” Carney said.

Oddly, as well as seeing no necessary relationship between size and safety, he also takes a lopsided position on this non-responsibility: while he is not responsible for determining the finance sector’s size, he nonetheless thinks that his role is to make it as big as it can be:

“The Bank of England’s task is to ensure that the UK can host a large and expanding financial sector in a way that promotes financial stability…” Carney said.

Herein lies the rub, and the non-sequitur: bigger cannot mean more stable, for the simple reason that the assets of the financial sector are, in large measure, the debts of the real economy to the banks. The bigger the assets of the financial sector, the higher the debts of the real economy have to be. Ultimately, even with near-zero interest rates, servicing this debt is likely to prove impossible to large segments of the economy, leading to a financial crisis.

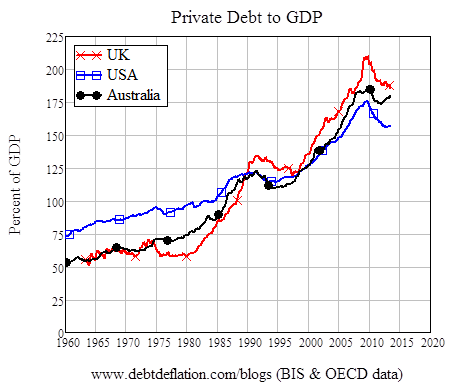

That logic is what led me to expect a financial crisis back in 2005: when I saw the data for Australia’s and America’s private debt to GDP ratios (figure 1), I was convinced that a crisis was in the offing. That rate of growth of debt compared to GDP could not continue. Figure 1 shows that I was right: the rate of growth of debt turned negative, ushering in the economic crisis that no central bank foresaw (except the Bank of International Settlements, thanks to its Minsky-aware research director Bill White). Debt to GDP levels fell as, for a while, the private sector deleveraged.

Growth is now returning -- strongly in the US, meekly in the UK -- largely because private debt is rising once more. But rather than seeing danger here, the UK’s central banker happily contemplates a world in which the UK financial sector is more than twice as big as it is now -- which would require the liabilities of the non-bank side of the economy to grow to roughly four times GDP.

Figure 1: The UK's Godzilla is bigger and faster growing than the US Godzilla

There is a line of thought that blames central banks for causing the crisis -- with Scott Sumner being the first to outright blame the 2007 crisis on Ben Bernanke. I don’t blame them for causing the crisis, but rather for letting the force build up that would make one inevitable -- by letting bank debt get much, much larger than GDP without batting an eyelid.

Now we’ve had the crisis, and if Carney’s speech is any guide, they’re once again letting private debt levels rip again, because even after the experience of 2008, they can’t see a problem. Given this complete failure of oversight, I expect that the sequel to the economic crisis of 2007 will appear before the next sequel for Godzilla.

Steve Keen is author of Debunking Economics and the blog Debtwatch and developer of the Minsky software program.