Finger-wagging at the wrong growth culprits

For the past three months there has been a steady chant of pessimism about growth prospects in the emerging economies, with the IMF’s voice prominent in the wailing. As IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde told the G20 meeting in September: ‘Just as some advanced economies have begun to gather momentum, many emerging markets are slowing’.

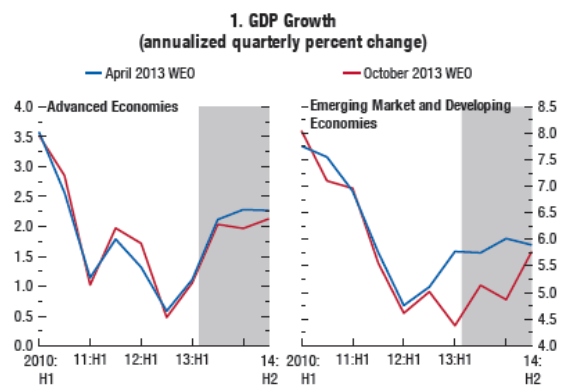

Now that the Fund has published its detailed forecasts, we can try to match the message with the numbers. Here is the emerging economies’ growth sequence, using the Fund’s fourth-quarter-on-fourth-quarter measure (which captures the shape of the cycle best):

The emerging economies slowed sharply beginning two years ago. The current year is expected to be a touch slower. Then the forecast shows acceleration for next year. The profile of these figures (see graph below) suggests that the sharp deceleration episode is now behind us. Whatever damage this slowing caused, we have already experienced it.

Of course the upturn next year may not happen. But even then, the Fund's narrative about emerging economies will be misleading.

The half-decade before the 2008 crisis was a halcyon era for emerging economies. Not only was China growing well in excess of 10 per cent, but India was not far behind and Brazil, atypically, was also doing well. The emerging countries came through the 2008 crisis much better than expected, with China’s huge stimulus helping to hold its growth close to 10 per cent in 2010.

But this was unsustainable, and to have the three biggest emerging economies simultaneously growing abnormally quickly was just fortuitous. The big deceleration came in 2011. By 2012 China was recording growth rates starting with a 7, India was down to 3 per cent and Brazil 1.4 per cent. Since then not much has changed. The Fund estimates China’s growth this year at 7.6 per cent, India at 4.9 per cent and Brazil at 1.9 per cent.

What has happened over the past year or so is not so much a slowing of actual growth (the slackening has been tiny). Rather, the Fund’s forecasts have been substantially revised to catch up with the reality that two years ago the emerging economies moved to a new growth plateau, lower than the pre-2008 halcyon era.

Since 2011, the emerging economies in aggregate have grown at a pretty steady pace of around 5 per cent. This represents a more realistic estimate of their sustainable underlying growth potential. Even this slower pace is still around three times faster than the advanced countries, and with their increased share of global GDP, their contribution to global growth is still as great as it was when they were growing faster but had smaller GDP.

The fact that the Fund has had to revise its forecasts is no big deal (forecasting is a thankless task). What matters is the policy narrative that accompanies the numbers. The gloomy dialogue is accompanied by finger-wagging admonitions to try harder. Sure, the emerging economies could do better if they were able to implement the Fund’s standard advice to implement substantial structural reforms. But everyone – emerging and advanced economies alike – finds this very hard.

It’s not sensible to bemoan the fact that these countries are not returning to the pre-2008 pace of growth. China cannot sustain double digit growth, nor can India get back close to 10 per cent without unattainable reforms. Brazil remains, perpetually, the country of the future.

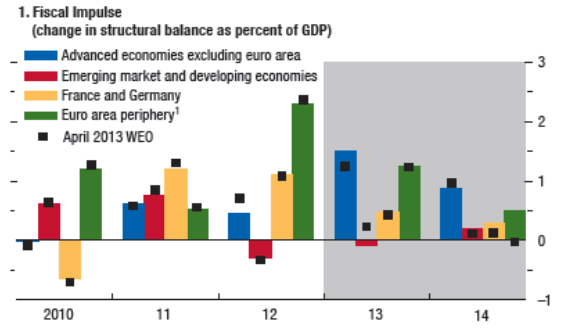

The laggards in this recovery are the advanced economies, and it is their deficient policies which need to be put under the spotlight. Lagarde's cheering message about the advanced economies taking the running in the recovery (she talks of ‘signs of hope from advanced economies – the United States, the Euro Area, and Japan’) ignores the reality that the European peripheral countries cannot recover without a huge writedown of their debt. European banks cannot support a recovery without more capital. Japan has done nothing about its official debt or tackled structural constraints. America and the UK would be going through a normal recovery, with above-average growth, if only they would take off the fiscal brakes. See this IMF graph showing the advanced countries, in blue and green, still in strong fiscal contraction into the forecast period:

As economic leaders meet in Washington to ponder the state of the world, the starting point should be to focus more sharply on the policy deficiencies in the advanced economies, or change the forecast figures.

Originally published by The Lowy Institute publication The Interpreter. Republished with permission.