Fill your nappies, we're turning Japanese

Given the ‘Kabuki-like' nature of budgets these days, with the drip-drip-drip of announcements prior to the event and tap-dancing politicians, equally smug or horrified after it, you shall read no more of it here. Instead, let's focus on disposable nappies.

Invented by Marion Donovan in 1946 using an old shower curtain, and patented in 1951 with the name Boaters, customers of US department stores loved it. Unfortunately, it wasn't a hit elsewhere. But Donovan knew she was on to something, as did Keko Corporation, which purchased her company and patents for $US1 million (almost $US10 million in today's money) a few years after Boaters hit the shelves.

Keko didn't make a go of it but a decade later Procter & Gamble launched Pampers, P&G's first billion dollar brand. As for Marion, she went on to patent a facial tissue box, a towel dispenser, cup holders in cars and flossing product – DentaLoop.

Lots of lives have been affected by Donovan's energetic mind but none more so than elderly Japanese people. In 2011, Unicharm, Japan's biggest nappy manufacturer, sold more nappies for adults than it did for babies. Why? Because 20 per cent of Japan's population is over 65-years-old – the highest in the world.

Japanese actors making adult nappies look cool. Source: Quartz (AP Photo/David Guttenfelder)

At 85-years-old, life expectancy in Japan is the second-highest in the world (Monaco - barely a country, but very rich - has the highest). Things like adult nappies and free iPads to remind them to pop their pills are having an impact. The buggers have almost stopped dying, which is worrying some politicians.

In 2013, Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso said: “I recently saw someone as old as 90 on television, saying how the person was worried about the future. I wondered, ‘How much longer do you intend to keep living?'”.

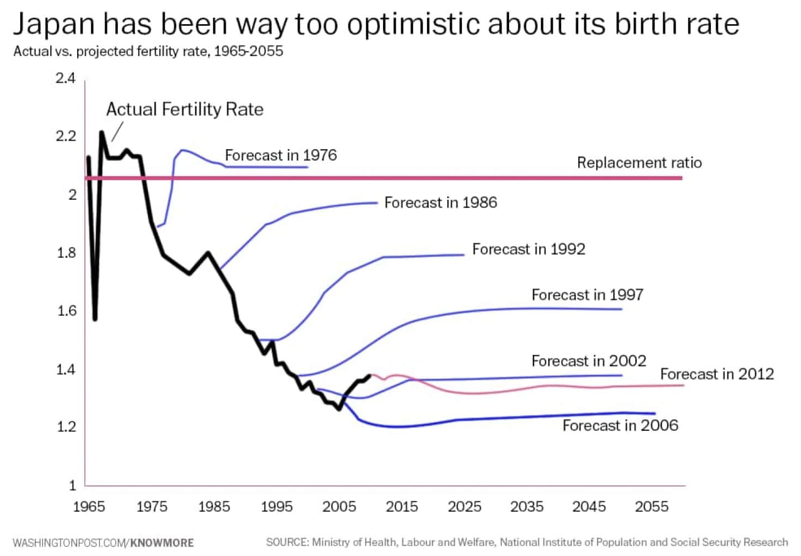

The problem of an ageing population is compounded by infrequent pregnancies, although that didn't stop a runaway pram from mowing me in a Tokyo park last year. According to the CIA, which, oddly monitors this type of thing, at 1.41 births per woman, Japan's total fertility is 209th out of 224 countries (Australia is 156th at 1.77). In Japan, fertility rates have been falling even faster than predicted:

This is understandable. Pregnancy costs aren't covered by Japanese health insurers, education is expensive, child benefits barely cover the cost of nappies, and childcare is expensive and hard to find.

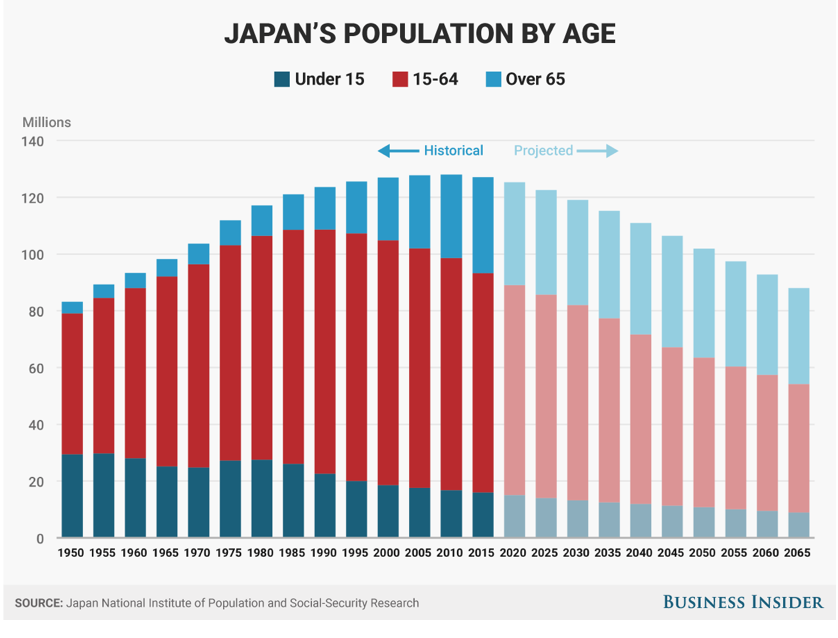

Instead, Japanese women are choosing careers over family, leaving lonely salarymen to rent part time wives and daughters (why didn't I think of that?). The collective impact of low birth rates and an ageing population is shown in this chart:

The overall population decline is less important than the compression of the red bars, which show the number of people of prime working age. Whilst travelling around the country last year, the impact of an ageing, shrinking population was everywhere. Except in Tokyo, which is still growing, building sites are a rarity.

Meeting a friend that had lived in Osaka during the 1980s, I asked her how it had changed. “It hasn't,” she replied. “It's exactly the same.”

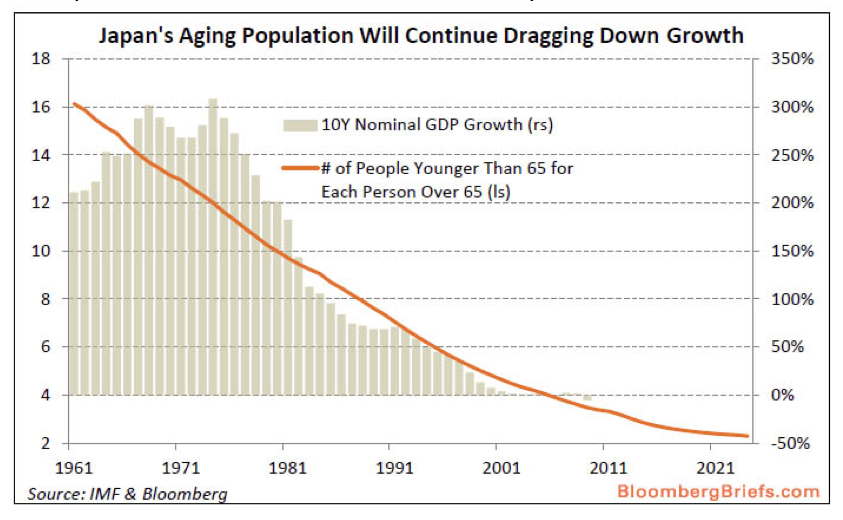

At first, it's baffling to travel in a famously hi-tech country and have your ticket marked with a pen by an 85-year old man, until you realise the reason for it. There's a lot of social and economic pressure to keep seniors in work. Here's a chart that explains some of the reasons for it:

Older people tend to save more of their money than spend it (just ask my kids). They don't work much, and they cost a lot more in healthcare expenditures than younger people. When a population ages it starts to skew all sorts of economic indicators.

The labour force shrinks along with the overall population, reducing demand and tax revenues at a time when more money is needed to look after the growing proportion of older people. In Japan, it's called the demographic time bomb and is leading to granny dumping and prisons that look more like nursing homes.

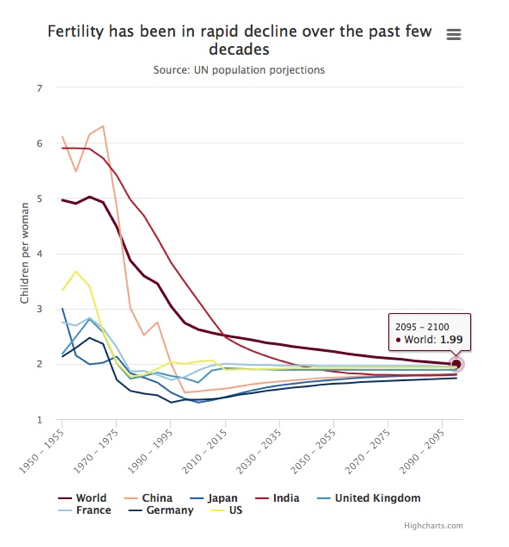

But here's the thing, Japan isn't an outlier. It's the future for all of us. Nearly half the world's population has fertility rates below replacement level. In the European Union, there are four working-age people to every pensioner. Within 50 years, that ratio is expected to halve. A vice president of the European Central Bank has called it “collective demographic suicide”.

Even in newly-industrialised China, where the fertility rate is just 1.5, the country “is in danger of growing old before it becomes rich". The United Nations estimates that by 2047, people aged 60 and over will exceed children, numbering more than two billion by 2050.

HSBC estimates low fertility rates and ageing populations will knock 0.6 per cent a year off global growth over the next decade compared with the previous 10 years. That's quite a chunk. The OECD, meanwhile, expects global growth of 2 per cent a year, over the next 50 years among OECD nations. Between 1950 and 2000 it was more than twice that.

Former Treasurer Peter Costello was onto this back in 2002 when he released Australia's first Intergenerational Report.

“By its nature demographic change arrives slowly”, said Costello, “but its effect is profound. Demography is destiny.”

So, what's to be done? Let's deal with the obvious solution to an ageing population, one adopted by Australia and neglected by Japanese immigration.

There are a host of reasons why immigration might be desirable, but fixing an ageing population is not one of them. Immigrants tend to have more babies than the average, but a generation later, unsurprisingly, the ensuing adults do not.

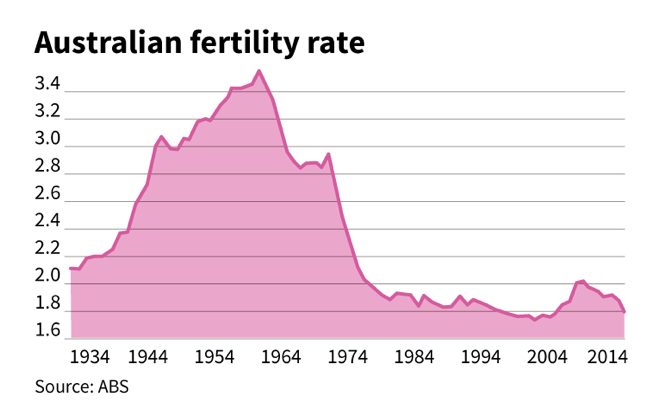

Over the long-term, immigration increases population, but it doesn't have much of an impact on fertility. If it did, the chart below wouldn't look like this:

In 2005, Peter Costello was urging young families to have three kids, and bribing them to do so. This may have produced a spike in the fertility rate, but it has not been sustained. Even the introduction of paid paternity leave in 2011 hasn't arrested the recent decline.

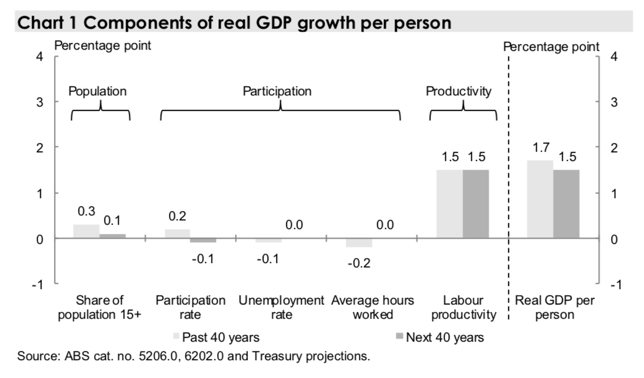

The 2015 edition of the Intergenerational Report makes clear the relative impotence of immigration and fertility to address the impacts of an ageing population on per capita economic growth.

The report states that economic growth will be slower over the next 40 years, compared to the last 40 years (but only slightly) due to lower projected population growth and declining participation rates. The key to getting through the cost and impact of ageing baby boomers, like me, will be increasing per capita GDP through higher workforce participation and productivity growth.

There's one country that is already doing this pretty well.

In Japan, unemployment is less than 3 per cent and, as per my experience last year, older people who want a job have one.

In Japan, 80 per cent of people who can work, do, compared with 70 per cent in Europe and the US. And the widespread use of robots, in assisting the infirm for example, is boosting productivity.

Japan isn't the basket case the headlines would have us believe. It is certainly not an example of “collective demographic suicide”, showing little social dislocation and suffering.

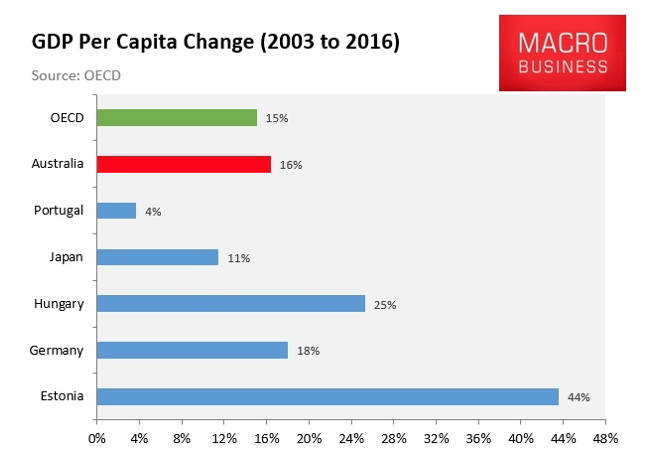

Since 2000, Japan's growth rate per working age person has been twice that of the US. This message doesn't get across because it's hidden by time bomb headlines that focus on absolute growth.

Once you account for a declining population (which, incidentally, helps to deliver cheap housing), to say nothing of deflation and the bursting of a huge asset bubble, Japan has done extraordinarily well.

In fact, Japan has achieved what our latest Intergenerational Report urges: “Ongoing improvements in Australian living standards will remain primarily contingent upon continually improving our productivity, and require us to take every opportunity to increase participation rates.”

That's to say, not Immigration and fertility, but productivity and participation.

There's one principal reason that might prevent us from following Japan's lead. The country's massive savings surplus finances its extraordinary public debt, which is now twice GDP. We don't have that luxury.

Still, if we're turning Japanese (I really think so), I'd settle for that. Just be prepared to save a little more and work beyond the official retirement age because, if Japan is any guide, we're all going to be living longer, more active lives, even if it means wearing nappies.

Enjoy your weekend and don't forget to take your pills.