Eureka's Week: Secular stagnation - what it is, how it happened, and what it means for investors. Plus: Brexit, China and BHP, Tax.

Last night | Secular stagnation | The role of population | What does it mean for investors | Brexit | Tax | Readings & viewings | Last Week | Next Week

Last night

Dow Jones, down 0.16%

S&P 500, down 0.10%

Nasdaq, down 0.16%

Aust. Dollar, US77.2c

Secular stagnation

The IMF actually used that term in its World Economic Outlook this week, warning that the danger of it has become “more tangible”.

In some ways I think it's just an expression of frustration, that this recovery from the 2008-09 crisis and recession has not turned out as normal or predicted – I guess we're all a bit inclined to catastrophizing things when we don't get our own way.

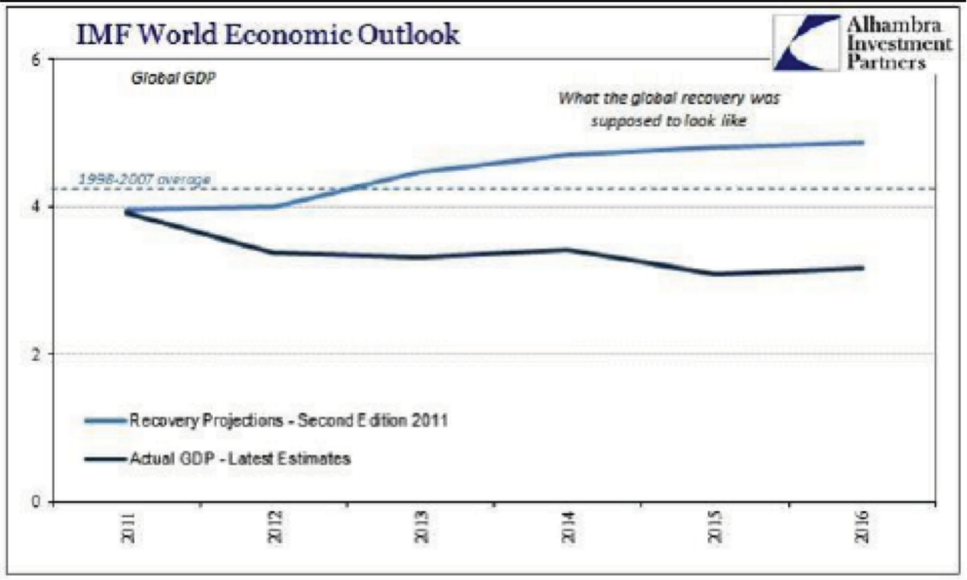

This chart shows how the recovery out of the GFC was expected to unfold:

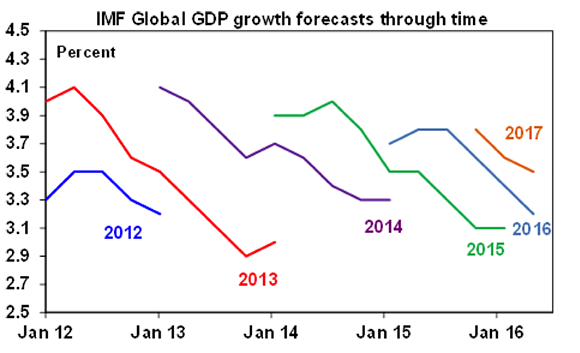

And this shows how the IMF's forecasts have had to change over time – its economists have consistently started out forecasting growth of four per cent and then has had to cut the forecasts as the reality of each year gets closer:

So today I thought I'd use this opportunity to look at what secular stagnation is, how it happened and what it means for investors. What's really going on, since the IMF is both behind the curve a bit, and a little too pessimistic. It's certainly taking the “glass half empty” approach anyway.

The idea of secular stagnation has been popularised lately by Larry Summers, who was US Treasury secretary between 1999 and 2001 (under Bill Clinton) and now professor of economics at Harvard University.

But the idea of secular (that is, indefinite) economic stagnation was first put forward by someone named Alvin Hansen in 1938. His theory, now adopted by Summers, was that economies in the industrial world suffer from an excess of saving and a loss of the propensity to invest.

That acts as a drag on demand which reduces both growth and inflation and that, in turn, pulls down real interest rates. When significant growth does happen – as it did between 2003 and 2007 in both Australia and America – it results from unsustainable bubbles. America's one of those – you know, the one that collapsed in 2008 – was a debt-fuelled housing bubble; Australia's was a commodities bubble that burst in 2012.

A Swedish economist named Knut Wicksell came up with the idea of the natural, or neutral, rate of interest (in the late 19th century) and essentially Larry Summers is using his work to propose that the neutral or natural interest rate has been declining and is now abnormally low: “secular stagnation occurs,” he says, “when neutral real interest rates are sufficiently low that they cannot be achieved with conventional central bank policies.”

In other words, market interest rates are too high, compared with the natural rate of interest, because central banks can't cut them any more.

Charles Gave of GaveKal has been doing a lot of research into Wicksell and the neutral real interest rate and has concluded that what matters for economies is not the absolute level of interest rates, but the difference between the market rate and the Wicksellian neutral rate.

In a recent research note he wrote: “If the market rate is too high relative to the natural rate, growth falters. If the market rate is too low, the economy enters an explosive cumulative process.” A bubble, or lots of bubbles, in other words.

According to Wicksell, during boom phases a lot of capital is misallocated and is destroyed in the subsequent bust.

Says Gave: “An economy which keeps market rates too low for too long will automatically find itself with less and less capital in cycle after cycle. Ultimately this capital destruction leads to a much lower structural growth rate, as the United Kingdom demonstrated between from 1966 and 1976, when London was forced to go cap in hand to the International Monetary Fund, and as we have seen in the US since 1998.”

Summers says there have been a number of factors that have increased the propensity of populations in developed countries to save and decreased their propensity invest.

“Greater saving has been driven by increases in inequality and in the share of income going to the wealthy, increases in uncertainty about the length of retirement and the availability of benefits, reductions in the ability to borrow (especially against housing), and a great accumulation of assets by foreign central banks and sovereign wealth funds.”

“Reduced investment has been driven by slower growth in the labour force (on which more below), the availability of cheaper capital goods and tighter credit (with lending more highly regulated than before).”

By the way, the quotes are from an article by Summers in Foreign Affairs magazine.

Summers' central argument is that the neutral rate of interest can't be increased through monetary policy. “Indeed, to the extent that easy money works by accelerating investments and pulling forward demand, it will actually reduce neutral real rates later on.”

This is a more sophisticated way of putting what I've been on about for a few months (see Central banks are destroying the world, 16 October 2015, and The wrong pig, March 18, 2016.)

The end point of the argument is that it is fiscal policy's turn to do something about stimulating the economy, which is also the central point of the IMF's WEO report this week.

In fact, as I pointed out on the ABC News on Thursday night, the IMF is now effectively begging governments to use fiscal policy to bolster failing monetary policy.

The main constraint on the world's economy, Summers writes, is on the demand rather than supply side. Keynes wrote in the 1930s that the cheapest way to increase demand is to promote business confidence so they invest and pay higher wages, about which there is plenty of talk but not much genuine action.

Thursday's labour market report from ABS continued the trend of rising part time work (mostly female) and falling, or flat, full time work. This is all about keeping wage costs low.

This year China will host the next G20 summit in Hangzhou. There was a good G20 in 2009 when those present agreed to do fiscal expansion, which helped get the recovery started.

But the bust had been misdiagnosed as cyclical rather than secular (indefinite). Subsequent G20s, including the one in Australia, returned (according to Summers) to their “traditional lethargy and misguided preoccupation with fiscal austerity, monetary normalization, and moral hazard, ending up missing opportunities to accelerate the recovery”.

The political classes in Australia, especially on the right, remain obsessed with fiscal austerity and the need to rein in budget deficits, even though the cost of borrowing has never as low as it is now. The return from virtually any infrastructure project funded with money borrowed by the government would be positive, probably extremely so.

So politics is fighting economics – that is, tight fiscal policy is offsetting the effect of reduced interest rates.

Is the world in secular stagnation, as Larry Summers says?

His answer, and mine: it looks the best and most complete explanation of what's going on, but not everyone agrees.

The role of population

Just before I get into the matter of what this means for investors, I just want to discuss a paper I've been reading this week about the demographics behind stagnation, by Ruchir Sharma, the head of emerging markets and global macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management.

His basic point is that between 1960 and 2005, the global labour force grew at an average of 1.8 per cent per cent, but since 2005 it has downshifted to just 1.1 per cent and will keep falling as fertility rates decline in most parts of the world.

“The implications for the world economy are clear: a one-percentage point decline in the population growth rate will eventually reduce the economic growth rate by roughly a percentage point.

“A collapse in the growth rate of working age population was already underway before the financial crisis and the trend explains a good chunk of persistently disappointing recovery since.”

In effect, Sharma is picking up one of Summers' points and expanding it.

Since 1960 the average number of births per woman worldwide has fallen from 4.9 to 2.5. This is partly due to rising prosperity and levels of education among women, but Sharma says it's mostly the result of aggressive birth control policies adopted in the developing world in the 1970s.

China introduced the one-child policy and the fertility rate fell from 3.6 to 1.5 today (which is below replacement level of 2.1). India embarked on a forced sterilisation programme in the 1970s and the fertility rate plummeted from 5.9 to 2.5.

Today nearly half the people on earth live in a country where the fertility rate is below the replacement level of 2.1. Over the next five years, the working age population growth rate will fall below the two per cent threshold in all the major emerging economies. In China, Poland, Russia and Thailand, the working age population will shrink.

Economic growth is much more difficult – in fact nearly impossible – when working age populations are shrinking, but it's also true that you need more than expanding population to have an economic boom.

Consider the Arab world. Between 1985 and 2005 its working age population grew at an average annual rate of three per cent, nearly twice as fast as the rest of the world. Yet the region never had an economic boom, and in fact many of the countries suffer crippling youth unemployment rates.

Anyway, many countries are trying to do something about it (Australia had the baby bonus, you'll remember, and China has dropped the one-child policy, not a moment too soon). Germany tried opening its doors to immigrants last year, but that backfired when a group of them started raping and sexually assaulting women in Cologne.

In any case, as Sharma points out, the contest to attract immigrants, particular skilled ones, is a zero sum game: one country's gain is another's loss, a bit like currency wars.

“The most governments can do is muffle the impact of depopulation; they can't defuse it.”

The good news is that the Malthusian nightmare of humanity being unable to feed itself won't come to pass, and robots stealing jobs might not be a problem either. In fact, automation might be coming in the nick of time – to replace the decline in working-age populations caused by unstoppable social and demographic factors.

What does it mean for investors?

The key thing is that if we really are in secular stagnation, interest rates will remain low for a long time.

The US bond future market pricing implies a bond yield of about one per cent for ten years. What's more, yields can't go much lower, especially in those countries that have negative bond yields already, so there aren't going to be a lot of capital for bond investors either.

So secular stagnation is bad for bond, or fixed interest, investors.

That means there will continue to be a premium for enhanced income strategies, such as “buy-write” funds, where call options are written against high-yielding equities to increase the income.

In general, continuing low interest rates combined with the rising number of retirees desperately looking for income means that premium prices are likely to be paid for assets that provide steady, reliable and preferably growing income streams.

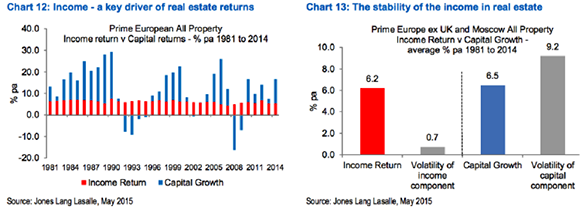

That means infrastructure and property – mainly because they tend to be less subject to market volatility, because they are unlisted and illiquid and therefore can't be played with by hedge funds.

For example here are a couple of charts I found in a Fidelity presentation:

This implies continued support for global real estate values. I'm not suggesting that Melbourne and Sydney apartment prices will keep rising (they won't) but broadly speaking there will continue to be support for real estate as an investment asset, as well as infrastructure.

Also, lower for longer interest rates imply higher share prices for two reasons:

- Bonds and equities tend to compete for the margin investor dollar and bonds will be out of favour, and

- Lower discount rates mean that analysts will increase their valuations for equities.

However there are a couple factors working against that:

- Sales growth for large established companies will also be slow in a low-growth world, which supports my argument against ETFs. Also lower discount rates increase the sensitivity to changes in cash flows.

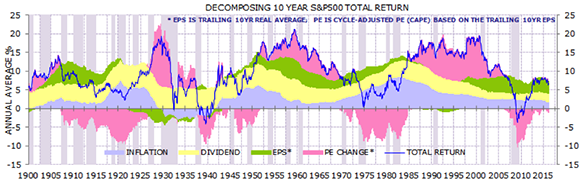

- Valuation alone is not a predictor of future returns from equities. Here is a fantastic chart from Gerard Minack, which deconstructs the 10-year total S&P 500 return since 1900:

It's clear from this that valuation change is the most volatile component of equity returns, even over the medium term.

Point one above implies that the marginal investor will be dissatisfied with normal, ETF-type equity returns and will be looking for something extra. I think that probably means portfolios will tend to contain more speculative stocks – for example, if a fund manager would normally have one biotech and one fintech in a portfolio for a spot of “blue sky”, that might be bumped up to two and two, or even three and three.

And also there will be more demand for unlisted start-up investments. We're already seeing that: the number of venture capital backed firms in the United States that are valued at $US1 billion or more has doubled in the past two years. There's an excellent WSJ infographic on this here: Billion dollar start up club.

Brexit

Britain votes on June 23 whether to stay in the EU or leave. There hasn't been a lot of interest in this in Australia, probably because most people at this distance don't believe the poms will actually do it, especially since both the Conservatives and the Labour Party are campaigning for “stay”.

Well, despite that, the leave case has been gradually gaining strength over the past 12 months and could actually win. Corporate support for staying in is, to say the least, lukewarm: only 36 companies in the FTSE100 signed up to a “stay” letter.

Does it matter to Australian investors? Yes, a fair bit.

Most UK economists reckon “Brexit” would be very damaging to the economy – GDP growth would drop by one percentage point or so. The pound would fall. UK equities would suffer. Banks would be suddenly flung into a world of uncertainty over cross-border regulations.

Here's a list of local companies and their UK exposure, courtesy Deutsche Bank:

CYBG (the demerged UK banks of NAB) – 100% of earnings

Henderson – 60% of assets under management

GBST – 45% of revenue

Iress – 27% of EBITDA

3PL Learning – 23% of revenue

Flight Centre – 15% of earnings

Computershare – 15% of EBIT

QBE – 12% of earnings

Ramsay – 10% of EBITDA

Brambles – 8% of revenue

Sonic – 5-7% of EBITDA

And the following companies have less than 5 per cent exposure:

Treasury Wine Estates

Ansell

Cochlear

Resmed

CSL

China and BHP

On Thursday night, BHP had surged 18 per cent in a couple of weeks, which is great news for those long-suffering subscribers who have watched as the stock halved last year.

I wrote a couple of weeks ago that resources would be a good place to be this year, and so it has turned out – so far. After sliding throughout 2015, the resources index is back at its six months high. Fortescue, especially, has been a bolter – doubling since January.

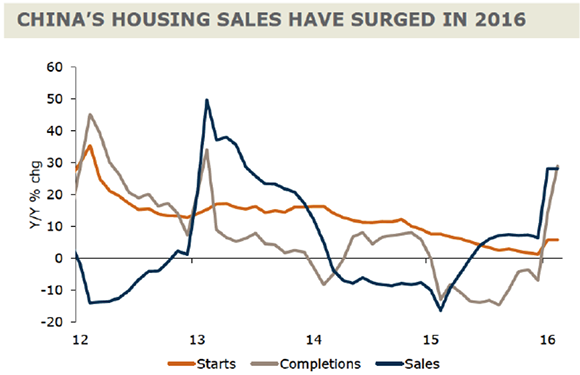

The reason is that markets are getting more comfortable about China. That's reasonable. The housing sector there has surged:

And yesterday the full March quarter data suite came out (a bare fortnight after the end of the quarter, as usual) and GDP growth was 6.7 per cent, which is smack in the middle of the Government's “target band”, if you believe it, which I don't. But it kind of doesn't matter what we believe and what the reality is – if the statisticians announce that Chinese growth is 6.7 per cent, then that's what it is. The wonders of dictatorship.

Anyway, industrial production rebounded from 5.4 to 6.8 per cent and retail sales grew 10.5 per cent. All good. No big, unexpected Chinese slowdown.

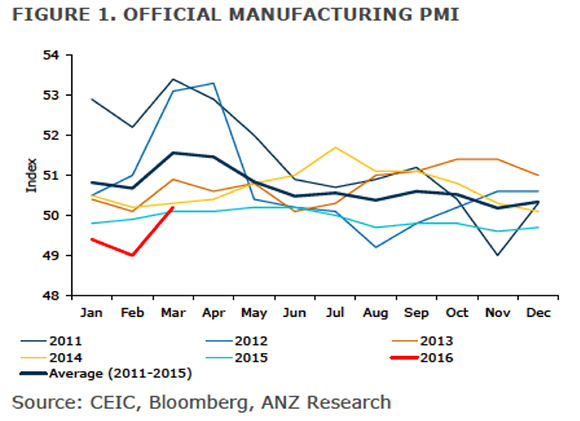

This all came after the March PMI on Thursday, which increased strongly – by 1.2 points to 50.2, well ahead of market expectations – although the starting point for 2016 is lower than previous years, as shown in this chart:

Government spending has also picked up, rising 12.2 per cent in January and February – partly due to the “One Belt One Road” thing I mentioned in March.

How long will all this last? That's the question. I do think we're probably in a long term commodities upturn, but there will be plenty of reversals along the way.

That's partly because of the earlier item about secular stagnation.

More specifically, China's chronic overcapacity, especially in steel, is a long way from being resolved. New technology is reducing costs, and allowing many managers to off closing down capacity. At the same time China's own economy is becoming less commodity intensive, so domestic demand is structurally weak.

But in a world of stagnant economic growth, the future of commodity prices, and therefore BHP's share price (and that of other resource firms), is all about supply, and one problem with this year's big commodity price rally is that it will slow down further supply shut downs, and might even bring capacity that had previously been curtailed.

Each market is a bit different: in iron ore profit margins would need expand a lot more for Chinese producers to imitate Lazarus; in industrial metals margins have improved very quickly so supply is coming back; in energy, there simply hasn't been the capital expenditure needed for a big rise in production.

Bottom line: The commodity rebound is fragile, and subject to the vagaries and mysteries of China, but it's there. BHP was oversold and has begun its price recovery with a bang. Stick with it.

Tax

Sometimes I despair of ever having decent government in this country. The Treasurer Scott Morrison, still with his L-plates on admittedly, has said that taxes are going to be increased, but not increased. Or they'll be increased in a better way than Labor would. Or they won't be increased in a bad way. That seems to mean, according to the leaks, taxes on tobacco and superannuation, but we can't confirm or deny anything. You have to wait till May 3.

He probably should just shut up, but that seems to be impossible. Look on all the ministers' websites and there are doorstops and interviews every single day, by every one of them. Blah blah blah.

As Laura Tingle wrote in yesterday's Financial Review: “Despite considerable experience around the cabinet table, the budget is being put together by people in the treasurer's office who have never had to do it before, just as the election strategy is being put together (at the government end, rather than party end) by people who have never had to do it before.”

I was at a conference in Sydney on Thursday ambitiously titled “Knowledge Nation” and the lunchtime speech was delivered by the Education Minister Simon Birmingham.

Nice man, but I don't know why he came. The speech was pure blather- absolutely zero content. These ministers, the PM and Treasurer included, seem to think they have to make a noise all the time or else they will collapse in on themselves and disappear.

Maybe May 3 will be the turning point.

Readings & Viewings

Amazing story: this bloke bought a motel so he could secretly watch people having sex. Even more amazingly, the journalist who has written the story for the New Yorker has known about it for years, but has only just written it.

The future will be quiet.

Notice something missing from the Panama Papers? Americans. And the reason for that is quite interesting.

But the question is: who benefits from the Panama Papers? That might be who leaked them. The thing is, nobody knows who, nobody knows why and nobody knows what, since the papers (or rather data files) have themselves not been made public.

But are the Panama Papers such a scandal?

To avoid disaster, we need to teach robots to disobey us.

In a cashless society, where money is just information, it can also inform on you.

Charles Darwin's list of the pros and cons of marriage (the cons outweighed the pros, yet he got married and had 10 kids).

Weak world leaders have created the monsters of Jeremy Corbyn and Donald Trump, and we're only one economic crash away from these two jokers gaining power.

For the golfers among you – a remarkable hole in one, sort billiards and golf in one.

And for the non-golfers (like me) here's Robin Williams explaining the game. Hilarious.

Tax: we doze, and out pockets get picked.

Not satisfied with occupying a whole lot of most peoples' time, Facebook is getting into the business of connecting them as well.

A Russian billionaire has backed an interstellar traffic project.

Here's why it won't work.

Bjorn Lomborg: Don't be fooled, Elon Musk's electric cars aren't going to save the planet.

University degrees are like mobile phones – you have to have one, but they're no big deal any more.

Really interesting piece that echoes that scene in The Graduate where Mr McGuire says to Benjamin, “I just want to say one word to you. Just one word.” Scientists of the future will have one word for the present: plastics.

And here's a video of that scene from The Graduate.

A Lateline segment presenting the case for and against sugar in our diets.

This is one those made up ads they do on Gruen Transfer – about multinationals paying no tax. It's a ripper!

As popular as Xi's battle against corruption has been among ordinary people, it has had an undeniably chilling effect on anyone hoping to speak truthfully to power.

Louis CK, my favourite comedian, is broke.

If the internet had never happened…

If you're baffled by ISIS, don't be. Spasms of barbarism usually happen when modernisation goes faster than civilisation is prepared for.

And from this week's Religion and Ethics report on Radio National – an anti-extremist muslim Imam explains the appeal of ISIS.

What does “ownership” mean in the digital age?

Gareth Thomas, the Welsh actor who played Roj Blake in Blake's 7, one of the finest sci-fi TV shows, has died! Bloody hell. But the remarkable thing about this BBC news video story about his death is that it is clearly voiced by a robot. Double bloody hell!!

This week's recipe: Donna Hay's chocolate meringue cake. Oh my.

Happy Birthday Peter Garrett, 63 today. Here he is doing the fabulous Beds are Burning, live in 2009. I think it was his last performance.

And here's his last speech in Parliament, in 2013.

Great rendition of This Train is Bound for Glory by Mumford and Sons, and a whole mob of others, sent in by subscriber Adrian. Thanks Adrian – it's great!

And just for the hell of it, a great Melbourne song – Weddings Parties Anything doing “Under the clocks”.

A rare picture of where Donald Trump grows his hair, in Tromso Norway:

Last week

By Shane Oliver, AMP Capital

Investment markets and key developments over the past week

Share markets pushed higher over the last week helped by a combination of better than feared US earnings results, good economic data and a continued unwinding of disaster fears from early this year. In fact the US share market is now up 2 per cent year to date. The “risk on” tone saw bond yields and commodity prices (except gold) gain with even the iron ore price making it back to around $US0.60/tonne. While the US dollar rose slightly the $A pushed back to around $US0.77 helped by stronger commodity prices and Australian economic data.

Surprise, surprise – the IMF has downgraded its global growth forecasts yet again to 3.2 per cent for this year from 3.4 per cent and to 3.5 per cent in 2017 from 3.6 per cent – adding to headline concerns about the global growth outlook. But just bear in mind that the IMF is just catching up to investor concerns that drove the financial turmoil early this year and in any case the IMF has been perpetually downgrading its growth forecasts for years now. See the chart below. Invariably the IMF starts off forecasting global growth for the year ahead to be around four per cent and then progressively revises it down to around three per cent. In other words the latest IMF growth downgrades are nothing new.

More significantly, a lot of the fears that drove markets lower earlier this year are still receding: Chinese economic data is looking healthier, those that really matter at the Fed are continuing to indicate that it will be cautious and mindful of global conditions in raising interest rates; the $US has come off the boil relieving pressures on emerging markets; the Chinese Renminbi is proving to be stable on a trade weighted basis; and fears around Eurozone banks appear to be fading.

It's coming up to Budget time again in Australia (May 3) and as always everyone is having their say, including the ratings agencies. The perpetual delay in returning the budget to surplus has not threatened Australia's AAA sovereign rating so far, but comments by Moody's expressing scepticism regarding the limited scope for meaningful spending cuts or tax reform suggest that ratings agencies may be starting to lose patience. Despite a commitment from both sides of politics to return to surplus it's hard to be optimistic about meaningful spending cuts unless the government faces a more cooperative Senate and meaningful tax reform looks dead in the water (again). However, there is some reason for optimism in that the cycle of each successive budget update pushing out the return to surplus may not be repeated in the May Budget as a higher iron ore price (it's now around $US60/tonne versus the MYEFO assumption of $US39) and stronger employment growth provide a bit of a boost to revenue. This is all about “parameter” changes though and the absence of a meaningful improvement in the structural deficit may continue to test the patience of the ratings agencies so the risk to the AAA rating may still rise. Would a downgrade to AA1 really matter? The experience following downgrades in other countries suggest the impact on bond yields would be limited but it could boost private sector borrowing costs marginally. And it would be a blow to the national psyche and would be a sad outcome given how long it took to regain the AAA rating after the downgrades of the late 1980s.

Major global economic events and implications

US economic data was mixed but okay. Jobless claims fell to their lowest since 1973 (the year Elvis appeared via Satellite from Hawaii), retail sales were softer than expected in March but previous months were revised up so not so bad, small business confidence fell and inflation readings were weaker than expected. Weak inflation readings support Fed Chair Janet Yellen's caution regarding signs of a pick-up in inflation and give it plenty of scope to go easy in raising rates. March quarter profit reports are off to a good start with 83 per cent of results so far beating on earnings and 57 per cent beating on sales. But its early days with only 30 S&P 500 companies having reported! Market expectations remain for a nine per cent yoy fall in earnings for the March quarter, but it's likely to come in a bit “better” at around -5 per cent.

The trickle of data suggesting Chinese growth is stabilising or improving has now become an avalanche. Chinese GDP growth for the March quarter slowed as expected to 6.7 per cent year, reflecting the weak start to the year. But the list of data showing stabilisation or improvement in March expanded further to include: PMI's, producer price inflation, exports, imports, electricity consumption, railway freight traffic, industrial production, retail sales, fixed asset investment and total financing. The bottom line is that the incremental stimulus measures of the last year or so are now helping growth. This in turn is being reflected in a stronger tone in commodity prices.

Australian economic events and implications

Australian data was surprisingly strong with solid February gains in housing finance for both owner occupiers and investors, a surge in business conditions to an eight year high and stronger business confidence according the NAB business survey and better than expected jobs growth pushing the unemployment rate down to 5.7 per cent in March. It's not all positive though as consumer confidence fell again in April to be well below its long term average and trend monthly employment growth has slowed to around 8000 a month from a high point of around 30,000 a month last year and hours worked are slowing. However, the fall in unemployment looks like a trend and it's hard to see the RBA easing against this backdrop. So a May rate cut looks unlikely. However, we continue to see a rate cut as likely for later this year to support growth particularly if the Australian dollar remains strong at a time when the contribution to growth from housing is slowing, the slump in mining investment is continuing, inflation remains around two per cent or below and banks continue to put through out of cycle rate hikes.

According to the RBA's latest six monthly Financial Stability Review the actions of regulators have led to reduced risks around housing lending but there are risks around apartment developments (notably in inner city Melbourne and Brisbane and increasingly Perth), some commercial property markets and around resource related companies. The bank's exposure to the resources sector is low though and risks around non-resources businesses are low.

Next week

By Craig James, CommSec

Reserve Bank dominates the agenda

The domestic economic data dries up over the coming week. In Australia the Reserve Bank will dominate the calendar and hopefully provide us with more insight on interest rates with the release of the Board minutes and also a speech by the Reserve Bank Governor. In the US the focus will be on the housing sector. And investors and traders will focus on the “flash” manufacturing data released across the globe (Friday).

On Monday, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) will recast the industry data on new car sales, converting the original data into seasonally adjusted and trend estimates. The Federal Chamber of Automotive Industries has already reported that 104,512 new cars were sold in March, down 0.5 per cent on a year ago. Interestingly we may be seeing a mixed picture on consumer spending but the same cannot be said for sales of sports utility vehicles (or four-wheel drive vehicles). It is clear that demand for SUVs is the main driver of vehicle sales, scaling new heights in March to be up over eight per cent on a year ago. In fact well over one in three new vehicles sold in Australia is a SUV.

On Tuesday in Australia, the minutes of the April 5 Reserve Bank Board meeting are released – the meeting that decided to leave rates on hold for another month. Investors will be hoping to get a better sense of central bank thinking from the Board minutes – particularly when it comes to the near-term economic and interest rate outlook. The statement following the ‘no change' decision in early April was mildly more upbeat, with the reduction in global financial market volatility certainly welcomed by policymakers. However the commentary suggested the door would be open for another rate cut if a super-low reading on inflation is published on April 27. We expect the minutes to focus on improving economic conditions, the policy outlook by the US Federal Reserve and the higher Aussie dollar.

In addition the Reserve Bank Governor Stevens will deliver a speech at the Credit Suisse 2016 Global Macro Conference in New York (11:30pm AEST). A title for the speech has not been released, but may focus on comparisons between the US and Australian economy and the drive for productivity in achieving growth targets.

The weekly consumer sentiment reading will be released on the same day (on Tuesday). Confidence levels have fallen for the past four weeks, down by 3.8 per cent. It is pretty clear that the uncertainty surrounding the Federal Budget and timing of the upcoming Federal election is dampening confidence.

On Thursday the NAB quarterly business survey is released alongside the March detailed labour market statistics from the ABS. The industry make-up of employment was released last month, but Thursday's data will have regional and demographic detail on the job market.

Overseas: US housing sector in focus; “Flash” manufacturing gauges

The flow of Chinese economic data has dried up, so the US takes centre stage in the coming week. And the focus will predominately be on the housing sector. However investors will also keep a close eye on the “flash” manufacturing gauges from across the globe.

The week begins on Monday when the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) index is released. Presidents of the Minneapolis and Boston Federal Reserve Banks deliver speeches.

On Tuesday, two key indicators on the housing sector will be released – housing starts and building permits. US annualised housing starts are tipped to have eased from a 1.18 million annual rate to 1.16 million in March. New building permits are expected to have edged higher in the month.

On Wednesday, existing home sales data is released and should have remained robust with annualised sales tipped to lift from a 5.08 million annual rate to 5.30 million in March.

On Thursday, the Federal Housing Finance Agency issues its February data on home prices alongside the weekly data on new claims for unemployment insurance, the Philadelphia Fed business index and the leading index for March. Home prices are currently 6 per cent higher over the year.

On Friday, the Markit “flash” readings on manufacturing activity are released in the US as well as Europe and Japan.

Share market, interest rates, currencies and commodities

The US earnings season cranks up a notch in the coming week. And while hopes aren't high for a good season of profit results, the contrarian view may prove more rewarding. According to FactSet estimates, earnings amongst S&P 500 companies are expected to slump by 8.5 per cent from a year earlier. Meanwhile Thomson Reuters estimates tip a 7.7 per cent slide in first quarter profits. Concerns for analysts and investors centre on the higher US dollar over the past year, low oil prices and the resulting hit to corporate profits, especially in the energy sector. But annual profit growth is tipped to rise over 2016.

On Monday, 38 stocks are expected to report including Hasbro, Netflix, and Morgan Stanley. On Tuesday there are another 72 companies listed including Goldman Sachs, Intel, Johnson & Johnson, and Yahoo!. On Wednesday earnings results are expected from 100 companies including American Express, CoreLogic, Mattel, Qualcomm and Coca-Cola. On Thursday 109 companies should issue profit results including KeyCorp, Novartis AG, Under Armour, Visa, and Verizon. And on Friday there are 42 companies listed including Caterpillar, General Electric, Honeywell, Kimberly Clark, and McDonalds.