Drawing on a Bondi cigar

Nowadays, the phrase “Bondi cigar” conjures images of a lactose-intolerant hipster drawing on a Cuban outside a beachside bar.

In 1990, before Sydney's offshore sewage outfalls had opened, it had a slightly different connotation. Let's just say the local fish were well fed.

Bondi was a comparative wasteland 25 years ago. Surfers would complain of paddling out among condoms and panty liners while the fatty smell of local milk bars mingled with fetid ocean odor. As I passed overflowing garbage bins and empty shops, I realised Bondi might be the only place where I could afford a unit.

Armed with a $30,000 deposit and a promise of $130,000 more from the bank, I landed on a large, two bedder; art deco style, crappy kitchen, wooden floorboards, two minutes to the beach. I missed out at the auction by $3,000 and retreated to the squalid delights of Kings Cross and Elizabeth Bay, never looking back on the episode until now.

The average price of a two-bedroom unit in Bondi is now $1.2 million. One close to the beach might fetch, say, $1.5 million. Over 25 years that's a compound annual growth rate of over 9 per cent. Not bad, especially when the capital gain is probably tax free and the place no longer smells of human waste.

My Bondi miss is a fair representation of what's happened to property markets generally, especially those in east coast cities, over the past quarter century. Prices have gone largely up, smashing inflation and the opportunity for anyone under the age of 35 to live in their own place.

.png)

Source: RBA

Anyone that has had all their assets in property – a really bad idea, of course – has done far better than those investing solely in shares (also a bad idea).

By 2006 I had capitulated, regularly ranting about the lunacy of Sydney property prices. My argument was both simple and naive; if one were to value property on the same basis as shares, it wasn't just sweet-smelling Bondi units that looked over-priced; so did everything else.

As former Intelligent Investor research director Greg Hoffman wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald in 2010, “parts of the Sydney market look 20-30% overpriced.” Greg, needless to say, is still renting. We were both howlin' at the moon, as the eponymous Bondi Cigars sang. Thinking that everyone else was mad for piling into a booming market, it turned out we were the maddies.

It is one thing to claim an asset is over-priced and another to predict its fall. Fortunately, Greg and I were in good company. House prices in Sydney and Melbourne have risen over 70 per cent since Professor Steve Keen predicted they would either be flat or fall between September 2008 and late 2009. In 2012, famed US fund manager Jeremy Grantham called Australian property an “abhorrent bubble”. Perhaps lost for words, he hasn't said much on the matter since.

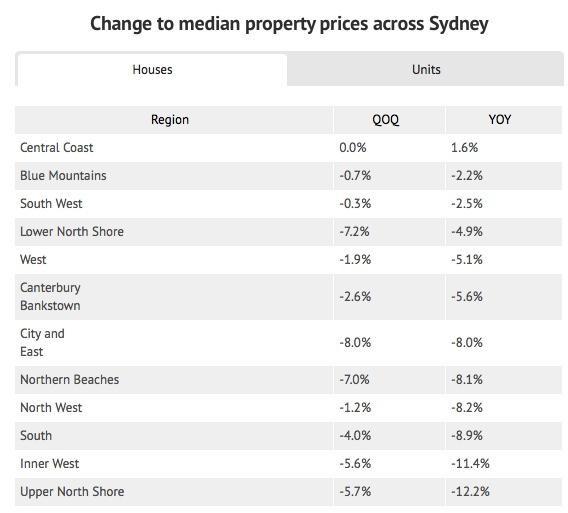

Having been trained by experience to expect house prices to go up indefinitely, the recent pull-back seems to be scaring the horses. “Sydney's housing bubble deflates as loans revisit GFC declines” was the AFR headline from June this year. Sydney prices are down, but it's hardly a crash.

Source: Domain June Quarter 2018 House Price Report

Bubbles only become so in the aftermath of their bursting. In my experience, using the term prematurely is unwise. Interest rates remain low and our population is growing, temporarily boosted by 400,000 foreign students on temporary visas (2017 figures). Land release in urban centres remains an omnishambles.

Most of us accept that Australia will eventually become a country of 40 million people, but we will fight to the death any plan to erect a 40-story block overlooking our backyard. As for the tax system, like a Bondi wheat beer, it is hand-crafted to favour property speculation over genuinely useful forms of economic activity. There's a lot of things propping up Australian property.

Ten years ago I thought house price rises couldn't persist for another decade. Nothing goes up forever, right? I sold a block in Sydney's eastern suburbs for a price perhaps less than a third of what it would reach now as a result. You won't catch me saying recent rises can't persist for a few more years.

A yield of 3 per cent on an investment property may look paltry, but it's looked that way for a long time. Keynes said that “the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent”. But given our recent history and current circumstances, who can categorically say Sydney and Melbourne's property markets are irrational?

This is not the tech boom; houses and apartments are real, as are the rents they generate. These are not flaky tech wreck era business plans carried aloft by a “paradigm shift”. Even students must live somewhere.

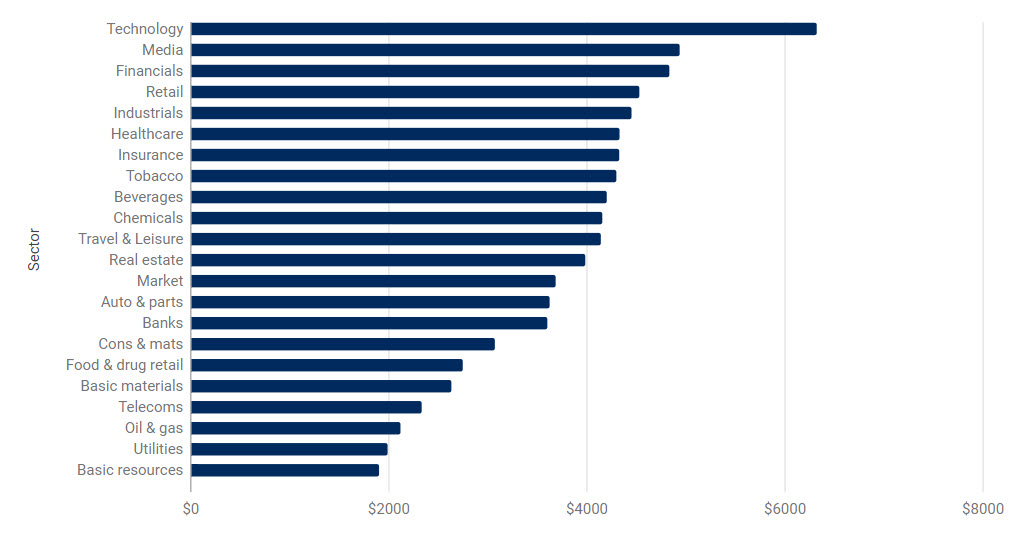

Which brings me to the current crop of stories speculating on the prospects of the longest bull market on record persisting. Schroders this week did the numbers. The US S&P 500 has risen 323 per cent from the lows of March 9, 2009, to August 20, Here's what $1,000 invested in global sectors between March 2009 and August this year is worth now.

Source: Source: Schroders and Thomson Reuters Datastream. Data for MSCI indices in local currency on a total return basis, unadjusted for inflation. Data at 20 August 2018.

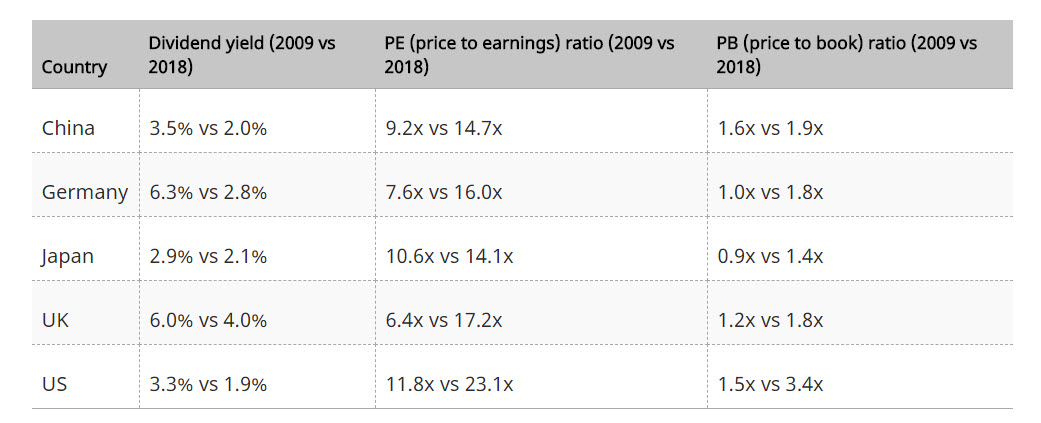

The so-called FANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google (now Alphabet)) are the biggest contributors to this astonishing increase, but former basket cases in media, financials and retail also feature. And here's the Schroder's data on what's happened to comparative valuations.

This might look familiar to local property investors. In what we might call the Fitzroy Effect, the price-to-earnings (PER) ratios of US stocks has more than doubled in nine years, slashing yields to less than 2 per cent. Japan has put in a more Adelaide-style performance, with the market PER increasing by a mere third. The only place offering a yield substantially above inflation is the UK, which is stuffed for its own unique reasons, a bit like Perth and Brisbane after the mining boom, where gross yields sit at about 5 per cent despite an oversupply of apartments.

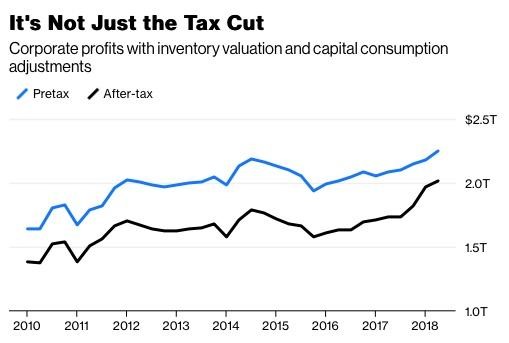

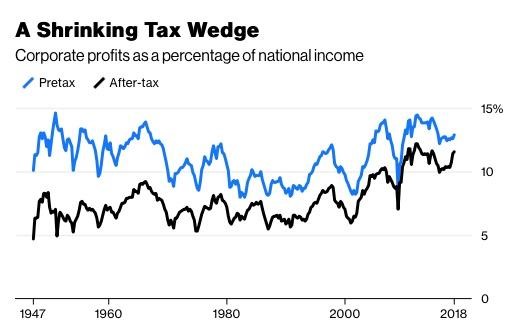

The US equities market and Australian property appear expensive. Are these valuations sustainable? In property, the juice comes from cheap money, tax incentives, limited supply and growing demand. In equities, higher valuations can only be sustained by higher corporate earnings. And yes, pre- and post-tax US corporate profits have been increasing.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, via BloombergOpinion

In a trend that is repeated across the globe, US corporate profits as a percentage of GDP and national income (which includes overseas income) have been steadily increasing for almost 20 years.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, via BloombergOpinion

If this trend in earnings growth falters valuations will fall, taking the longest ever bull run with it. There's another problem, one I've referred to previously; most of the increase in corporate profits is being returned to shareholders through higher dividends and share buybacks.

Very little is feeding wages growth or investment. This is not a recipe for a prosperous future. That being so, I suspect the prospects for mean reversion in stock valuations are stronger than they are in local property (no, this is not a prediction).

In Australia, higher valuations have had an equally impressive impact. There are now just seven stocks on our Buy List, the lowest number ever. Why not sell up and head to Bondi for a few years until the madness subsides?

There are two reasons. First, as I hope the revelations of my flawed approach to property reveals, it's a mistake to think high valuations can't march higher. In selling out you're effectively trying to time the market, which is never good.

I have been selling down stocks that have risen beyond reasonable value, but nothing more. In my view, going to cash carries more danger than staying in attractive, growing businesses over the long term. If that means I have to wear a 25 per cent fall every now and again, so be it. Had I adopted this approach with property I'd be much better off.

Second, whilst there may be only six stocks on our Buy List now, there will be more over the next 12 months and I want to be ready for them.

Investors cannot control immigration or urban development policies, corporate tax rates, wages growth or interest rates. What we can control is what we buy and sell and the mindset we bring to the process. That's worth worrying about; the rest of it really isn't.

Enjoy the weekend.