Copper travels down the iron ore road

Summary: Big miners are ramping up their copper production, but too much supply can only have one outcome. The copper price has already fallen. |

Key take-out: Copper producers with low-cost operations would survive and prosper in an oversupplied market but would not produce bonanza profits. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Commodities. |

History can have an unpleasant way of repeating, which is why shareholders in BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and other copper miners should keep their fingers crossed that the economic forces that savaged the iron ore industry do not do the same to copper.

The issue is as simple as supply and demand, turbo-charged by an inexplicable belief held by some mining-company managers that they are operating in a vacuum, unaffected by what other miners do.

In more simple terms copper has become the “go to” commodity, complete with forecasts of a strongly rising price. But the principal problem is that everything being said today about copper was said about iron ore five years ago, before oversupply crashed the market.

Both BHP and Rio, along with Glencore, Anglo American and China's MMG (formerly known as Minerals and Metals Group) have earmarked copper as their preferred metal for exploration and project development.

In the case of BHP and Rio, that means re-allocating capital away from iron ore to copper projects, such as the expansion of the giant Escondida mine in Chile and the Oyu Tolgoi mine in Mongolia.

Early warning signs

An early sniff of a potential copper glut came last month when Swiss-based Glencore reversed an earlier decision to cut copper output when it unveiled a 20,000 tonne-a-year increase in its previous forecast for 2016 copper output to 1.41 million tonnes.

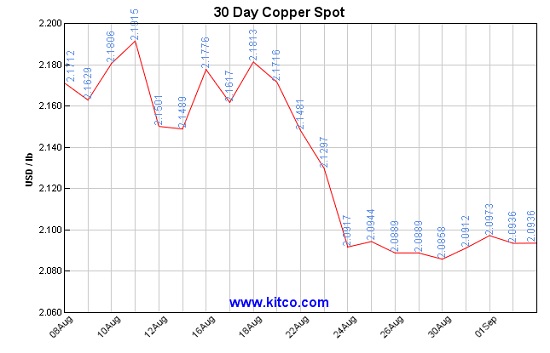

A second warning sign emerged a week later when the copper price nose-dived from around $US2.18 a pound to a 10-week low of $US2.08/lb, appearing to have resumed a plunge which started in 2011 when the price was more than $US4/lb.

Global stockpiles of copper are currently at their highest since October last year amid reports that demand in China, the world's biggest single user of copper, has stalled. This prompted some analysts to revise their predictions that a lack of investment in new mines would lead to a copper shortage next year.

The latest forecast from credit ratings agency S&P Global Ratings is that copper will remain oversupplied this year, with a recovery delayed until 2018.

UBS, an investment bank, sees the copper market shifting from a modest oversupply of 227,000 tonnes this year to a small deficit next year, and for the three years after that, before returning to a substantial surplus of 440,000 tonnes in 2021.

Who's right in the production and price tipping game is irrelevant in taking a long-term look at copper through the prism of what the same mining companies expanding in that metal said about iron ore in 2011. Back then, forecasts of strong Chinese demand triggered an industry-wide mine development boom.

More copper expansion

In the case of BHP copper sits alongside oil as the preferred target for new investment, with three copper projects named in the company's top five expansion opportunities. These are the expansion of Escondida (jointly with Rio) and Spence mines in Chile, and Olympic Dam in South Australia. The other two highly-ranked opportunities are more iron ore in Western Australia and the Caval Ridge coal project in Queensland.

Exploration targets, which point to where BHP expects to find its next crop of mines, are dominated by copper and oil with additional tenements acquired in Peru and the southwest of the US for copper.

Rio is on the same wavelength as BHP when it comes to copper, with a clue to intent lying in the appointment of Jean-Sebastien Jacques, the former head of the company's copper division, as its new chief executive.

In a paper delivered last year while head of copper, Jacques spoke of “creating leading copper and coal businesses” which focused on expanding existing mines (Oyu Tolgoi, Grasberg, Escondida, and Kennecott in the US), plus working towards two new world-class copper mines: Resolution in the US and La Granja in Peru.

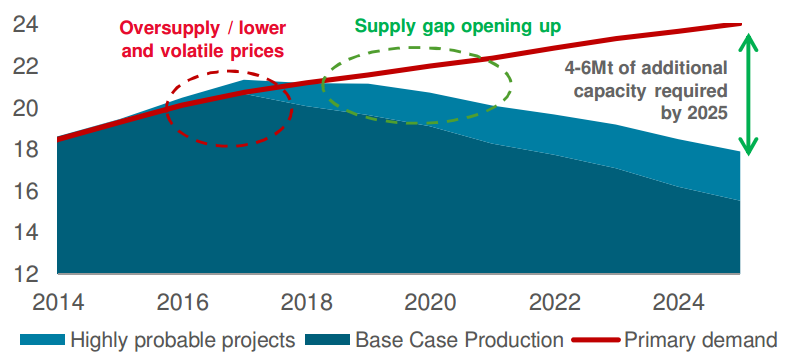

Rio Tinto's forecast copper supply/demand, June 2015 (million tonnes)

Source: Rio Tinto copper and coal roadshow presentation, June 2015

But what Jacques said 15 months ago, and the graphs he used to justify his optimism, are looking less attractive today.

Jacques argued that supply disruptions of 6 per cent a year (mine closures and shipping delays) would help boost the copper price as Chinese demand continued to grow.

But since then the copper price has fallen from around $US2.75/lb to its current $US2.09/lb and analysts at the investment bank Morgan Stanley have questioned the assumption that supply disruptions will be as high as Jacques forecast, adding to the oversupply problem.

“Copper mine supply through the first half of 2016 has marginally outperformed our expectations, with disruptions tracking at 1.8 per cent year-to-date,” Morgan Stanley said.

“If this low rate of disruption continues through the second half of 2016, mine supply will exceed our initial forecast by around 230,000 tonnes in 2016 (which will be) bearish for the copper price.”

Banking on the next cycle

What the big mining companies are banking on is a shared belief that the copper “cycle” of over-and-under supply runs in seven-year cycles which, in theory, means that copper is close to the end of the current down leg in the cycle.

Deutsche Bank argued in a mid-year study of the copper market that as fundamentals reasserted themselves, an upward price leg would start with the price moving back towards $US2.70/lb in 2019.

Given the widespread uses of copper in a range of industries that include electronics, transport and construction it is hard to dismiss the optimism shown by the mining industry and investment banks towards copper – if it wasn't for the fact that the same people said the same things about iron ore five years ago.

Back in 2011 BHP, Rio, Fortescue Metals and Anglo American were engaged in a furious race to expand their iron ore mines because they all subscribed to the theory that Chinese demand would underpin a period of growth and high prices. This was simplified into the slogan of “stronger for longer”.

The iron ore stampede produced an inevitable oversupply, which hurt shareholders in all producers of the mineral, and has led to what looks likely to be a decade-long glut. It will be a time when only low-cost mines can produce profitably.

BHP, Rio and Fortescue will successfully ride out a prolonged iron ore downturn, which is expected to see the price settle in a range of between $US40 a tonne and $US50/t.

Copper is travelling on the same road and while companies with low-cost operations will survive and prosper it will not produce bonanza profits for the simple reason that too many mining companies have decided at the same time to pursue copper expansion programs.

The UBS copper “model”, measured in days of total inventory (stockpiled material) is for this year's inventory of 50 days supply slipping to 44 days by 2018, 41 days in 2020 – but then rising back to 47 days in 2021 as supply from new mines such as those being developed today by BHP and Rio hit the market.

The problem confronting all mining companies is that projects conceived in the boom years have generally satisfied the market and look like doing so for some time.