Coal powers on amid competing forces

Summary: Changes in Chinese policy and some halts to supply in Australia and Indonesia have coal prices - especially metallurgical - rising. |

Key take-out: It is possible, much to the annoyance of the environmental movement, that a sustainable coal revival is underway after five years in the sin bin. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Commodities. |

Coal is up, though the popular view is that it will soon fall again, but whether that's true is a question worth exploring because there is a case to argue that the commodity the world hates is also the commodity the world cannot function without.

It is possible, much to the annoyance of the environmental movement, that a sustainable coal revival is underway after five years in the sin bin thanks to sharp falls for both major types of coal: thermal used to produce electricity and metallurgical used to make steel.

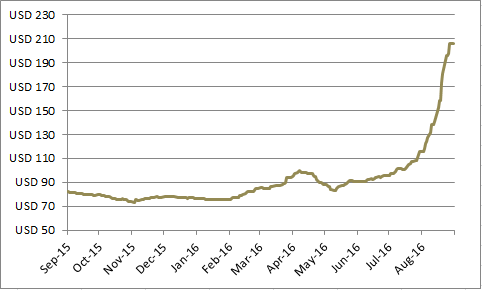

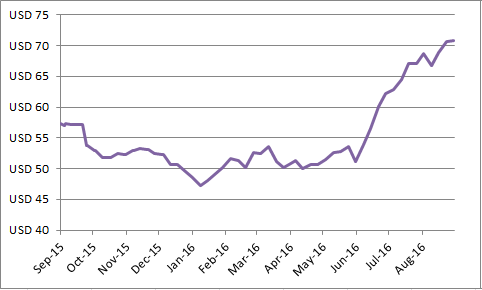

Thermal coal fell from a peak of $US150 a tonne in late 2010 to around $US40/t earlier this year. Metallurgical coal crashed from almost $US400/t in 2011 to $US55/t late last year.

The bounce since those low points has been remarkable. Thermal coal has come close to doubling to $US70/t and metallurgical coal has done even better, rocketing up by 250 per cent to more than $US200/t.

Charts 1 and 2: Metallurgical (top) and thermal coal prices

Source: Bloomberg, Eureka Report

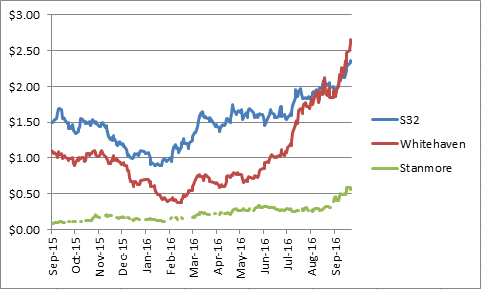

The handful of ASX-listed coal stocks have reacted quickly to the higher prices. Whitehaven (WHC), the locally-listed leader, has more than doubled since June 30 from $1.07 to $2.49. Stanmore (SMR) has done almost as well, up from 27c to 59c over the past month. Yancoal is up from 10.5c to 24c, and South32, the BHP Billiton spin-off, is up from $1.80 to $2.30.

The immediate cause of the coal revival is a change in Chinese Government policy introduced in March and designed to achieve two objectives; the elimination of small, inefficient coal mines which have helped depress the price and threaten the viability of the broader coal-mining industry, and as an environmental clean-up measure.

The key plank in the policy has been to limit mines to 276 days of production each year, an order which has helped shrink stockpiles of surplus coal, but has also led to shortages of certain types of coal, especially steel-making metallurgical quality material.

That Chinese policy coincided with problems at a number of Australian mines which limited production and flooding in Indonesian mines, adding to concern about supply reliability, especially for metallurgical coal which is essential in the steel-making process, forcing some steel mills to make panic purchases or risk closing blast furnaces.

Changes to the 276-day policy have recently been announced with 74 mines permitted to produce more than their quota as part of a government plan to match supply with demand to achieve a balance for both producers and consumers.

It is the tweaking of the Chinese policy which has prompted predictions that the recent upward surge in coal prices could be short-lived and that Australian-listed coal mining stocks will see their share prices soon retreat.

Chart 3: Australian coal stocks rising

Source: Bloomberg, Eureka Report

That could be a correct call in the short term, but in the long term it is likely that a coal shortage could develop thanks to worldwide policies aimed at discouraging the use of coal.

The pressures on coal

The effect of on-off Chinese coal production policies, coupled with low prices during the recent period of oversupply, has seen widespread mine closures, job losses, and a collapse in mine development plans.

In Australia, the best example of a proposed coal project struggling to win a final development decision is the Carmichael mine of India's Adani Group.

In theory, Carmichael has cleared all of its approvals but whether Adani is prepared to spend $16 billion on what could become one of the world's biggest coal mines, producing 60 million tonnes of mainly thermal coal for the Indian power industry, seems unlikely.

Whatever the cause of a go-slow (or cancellation) at Carmichael the key point for other coal-mining companies is that an annual 60 million tonnes of competing coal has effectively been withdrawn from the market, and that also means another four coal mines planned for Queensland's Galilee Basin are unlikely to proceed.

With new mines struggling to win government approval, and with policies designed to discourage the use of coal, a clash is developing between popular environmental policies and the need to produce enough electricity at the right price to keep industry functioning.

South Australia got an early wake-up call when its policies of closing a coal-fired power station and reliance on wind and solar as sources of energy exposed its industrial base to sky-high power prices.

The SA power crisis produced polarised opinions about the cause with the environmental lobby claiming it was not a result of closing coal and gas-fired power stations, and industry saying it was.

Similar arguments are being heard around the world as countries try to move off reliance on coal to a greater use of renewable power sources, with mixed results and often with sharply higher electricity costs.

Germany is trying to shift its economy onto renewable power, but has been forced to also burn record amounts of brown coal to plug a shortfall in electricity supply.

It is possible that over time new sources of electricity will replace coal, and that modern power storage devices such as lithium batteries will overcome the reliability problems of solar and wind.

But when the changeover to reliable renewables might occur, and whether the new power sources will be able to meet the demands of industry, is unknown.

Until then, coal will retain its role as a preferred, affordable and reliable source of power with demand expected to grow (rather than decline) as a new generation of High-Efficiency, Low-Emissions (HELE) coal-fired power stations are built, especially in Asia.

This new generation of HELE power stations will require high-quality thermal coal of the sort mined in Australia.

It is a complex equation and one being clouded by misleading and exaggerated claims. Environmentalists are getting ahead of themselves with claims about renewables and governments are making power supply promises they can't keep if they force the closure of coal and gas-fired power stations.

In effect, there is a fascinating debate underway in which political populism is bumping up against the laws of supply and demand as explained by the Scottish economist, Adam Smith, some 250 years ago.

Shortages, of the sort created by Chinese Government coal-mining policies and mine closures in Australia and elsewhere, will inevitably lead to higher prices which should encourage additional supply – but not if government policies prevent it.

It is a cocktail of competing forces but it's also one that seems to be suiting Australia's coalmining industry, for now, and perhaps for some time as the renewable power industry struggles to deliver on its promises of reliability and of being able to meet the demands of industry.