Budget narrative vs budget reality

Summary: The Budget remains a document dedicated to constructing an economic and fiscal narrative rather than describing an economic and fiscal reality. |

Key take-out: There's an argument the government should be pursuing expansionary fiscal policy, despite the likelihood of a credit rating downgrade. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Economics. |

The release of the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) wasn't a disaster but it is clear that the Federal Government still has a revenue problem that has not been addressed. Until this problem is addressed, the government will find it almost impossible to drive the budget towards surplus without also running the economy into the ground.

The good news is that MYEFO revised down the federal budget deficit in 2016-17 to $36.5 billion from $37.1bn at the release of the Federal Budget in May. The bad news is that in aggregate the budget balance was downgraded by $10.4bn over the next four years.

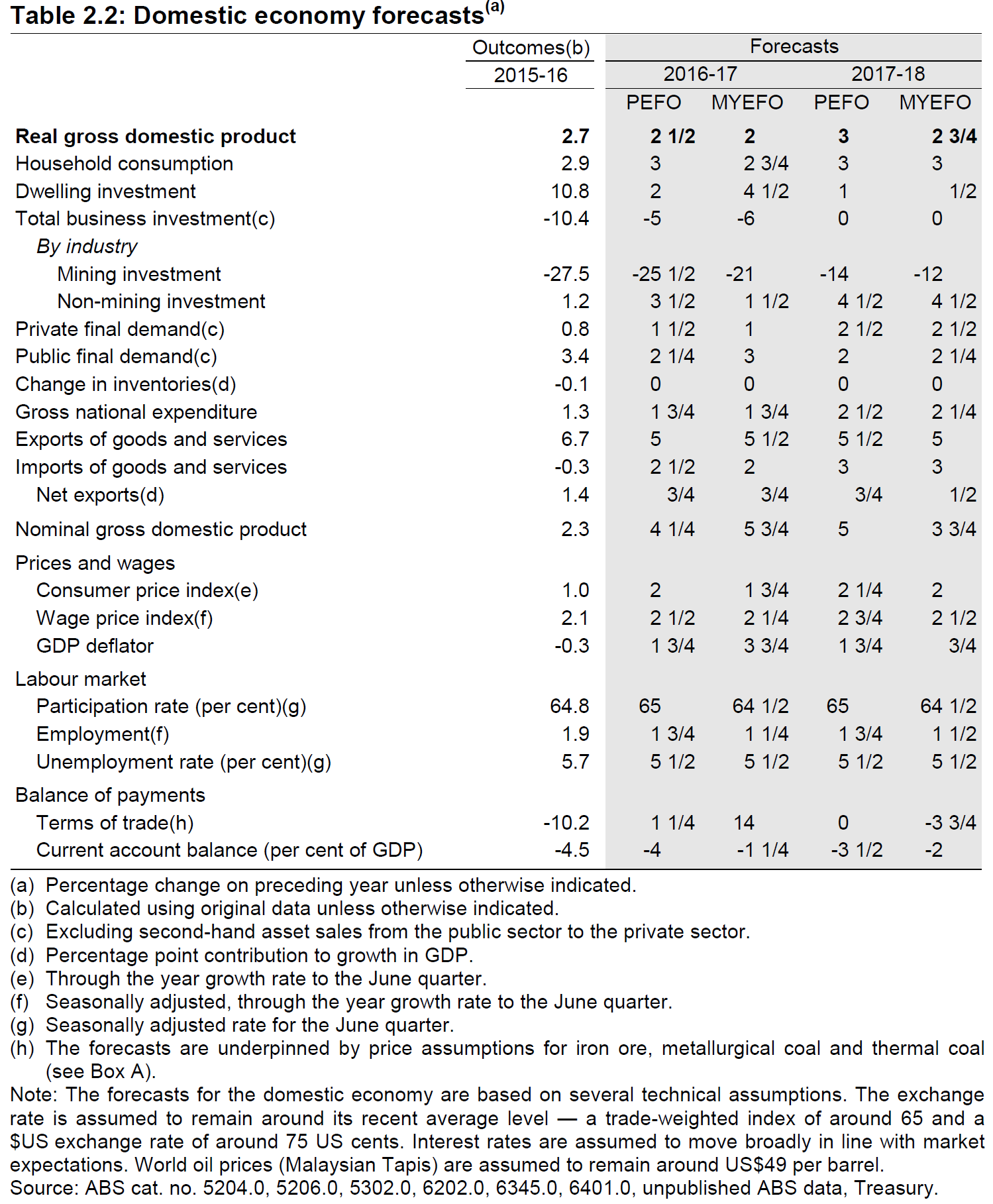

The economic forecasts that underlie the Federal Budget are contained in the table below. The forecasts for MYEFO are compared against the forecasts contained in the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook (PEFO).

Real GDP growth has been downgraded in 2016-17, owing in part to the 0.5 per cent decline in the September quarter, and was downgraded further in 2017-18. Inflation and wage growth is expected to remain weak over the forecast horizon, with both downgraded in the MYEFO update. Improvements to the terms of trade has helped the bottom line but wasn't sufficient to offset the weakness in inflation and wages.

The Federal Budget remains a document dedicated to constructing an economic and fiscal narrative rather than describing an economic and fiscal reality. The government was criticised in May on the grounds that its forecasts were too optimistic – an allegation since proven correct following the most recent set of downgrades – and a similar charge can be made against the MYEFO update.

Standard & Poor's made that clear with their comments after the release of the MYEFO estimates.

“We remain pessimistic about the government's ability to close existing budget deficits and return a balanced budget by the year ending June 30, 2021,” said S&P Global Ratings in a note released on Monday.

That pessimism is justified. We have now experienced eight years of regular and predictable budget downgrades. Each year since the global financial crisis has included promises that budget repair was imminent; that revenue would return to the highs established during the commodity price boom and that expenditure was under control.

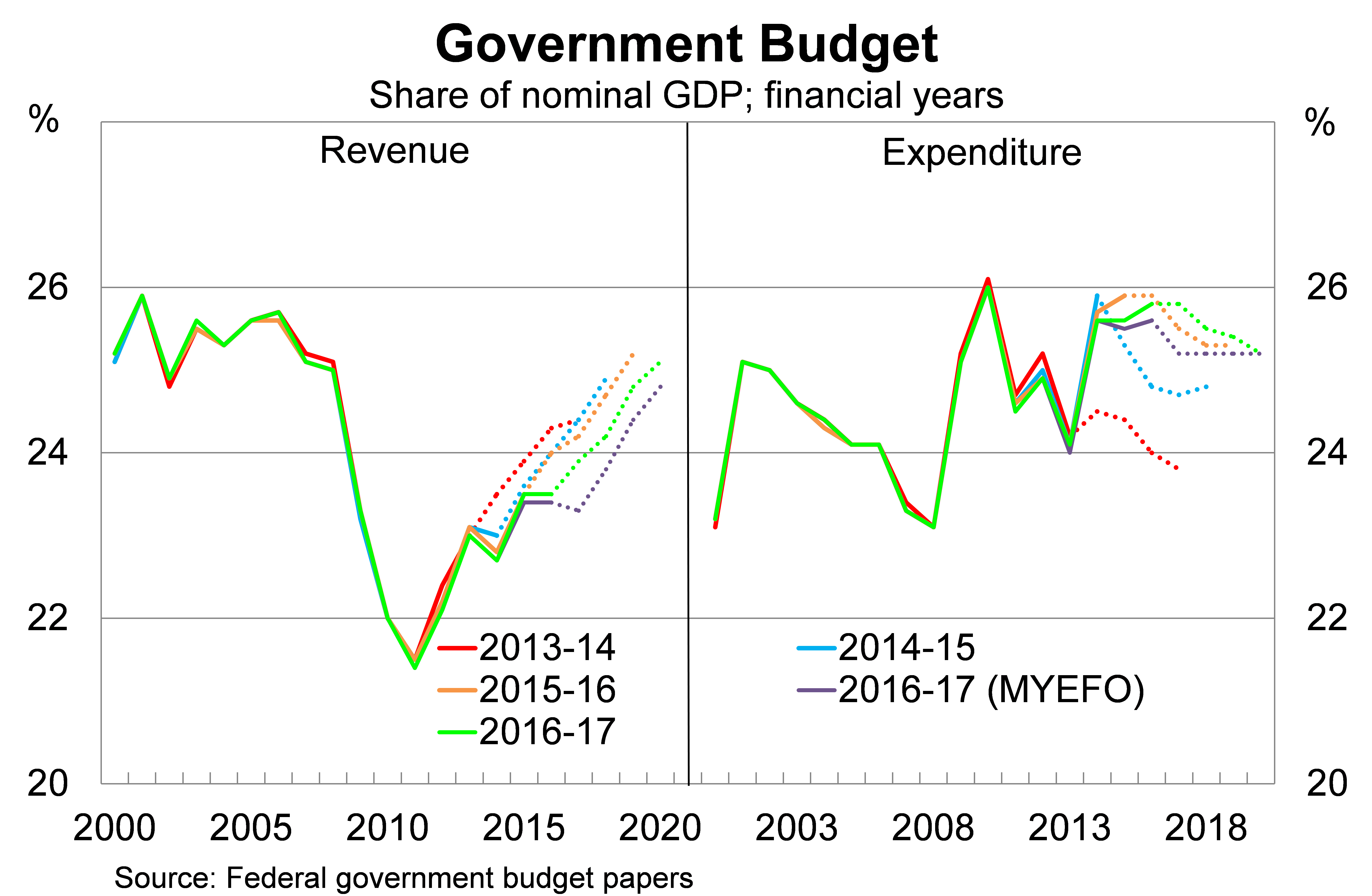

The graph below compares the revenue and expenditure forecasts contained in the Federal Budget since 2013-14. Revenue has been downgraded by $30.7bn over the next four years. By comparison, expenditure estimates have been revised down by around $20bn. Leaving us with a deficit that is $10.4bn higher over four years.

The ongoing assumption for revenue is that it will return towards its pre-crisis level. This is a common assumption in economic forecasting – known as mean reversion – but it is a dangerous assumption given the ongoing structural change facing the Australian economy.

The high levels of tax revenue obtained during the second half of the John Howard government were a product of a once-in-a-lifetime commodity price boom; supported by favourable demographics and strong population growth.

Those three factors have shifted in the opposite direction since the global financial crisis – despite the recent pick-up in commodity prices. An ageing population and softer population growth, combined with weaker profits and wages, have conspired against the Federal Budget. The government is betting – as they have done each year since the global financial crisis – that these trends are temporary.

There has also been some creative accounting on the expenditure side. As noted above, expenditure was downgraded by around $20bn over the next four years. However, only $2.5bn is attributable to policies enacted or proposed by the Federal Government.

The remainder is attributable to revisions in existing policies. For example, the government expects to spend $7.6bn less on childcare benefits over the forward estimates. They also expect to spend $2.7bn less on pension payments.

Revisions are fine and the budget should reflect the best available information. But it can be dangerous to extrapolate short-term trends, particularly when they are used for political means.

Growth in pensions may have been a little weaker than expected over the past year but with an ageing population do we really expect that to continue? We should certainly have our doubts and ideally the government should have applied more conservative estimates.

Should we even run a budget surplus?

My discussion so far has mainly centred on the validity of the numbers featured in the budget. But I wanted to turn my attention to whether we should even be targeting a budget surplus.

The Australian public has been conditioned to believe that running a budget surplus is the very definition of sound economic management. This ignores the fact that Australia has run a regular budget deficit throughout its history; the main exception being during our terms of trade boom last decade.

With economic growth quite weak – annual growth is at its lowest level in seven years – and household balance sheets stretched, it may actually be dangerous for the federal government to pursue a budget surplus.

To explain why, I wanted to turn our attention to Australia's current account. The current account basically describes the balance of a nation's savings and investment. When the current account is in surplus, as in the case of countries such as China and Japan, a nation is saving more than they invest and is therefore a net lender to the rest of the world.

For a current account deficit, as in the case of countries such as Australia and the United States, the opposite is true. Australia has historically borrowed from the rest of the world to finance infrastructure programs and fund bank lending. More recently we have relied on foreign capital to finance our residential construction boom.

Since Australia's current account deficit is roughly equal to public sector plus private sector borrowing, Treasurer Scott Morrison's commitment to returning the budget to surplus has important implications for national investment and growth.

Morrison's budget and the MYEFO update is predicated on the idea that households and businesses will take on greater debt to offset the reduction in government borrowing. With households already stretched – household debt in Australia, as a share of nominal GDP, is the third highest in the world – the government is relying on businesses to borrow heavily to support domestic demand.

If this doesn't happen then any attempt to reduce the budget deficit will lead to a sharp fall in economic growth. We have already seen growth ease throughout this year as our current account deficit narrowed.

With the non-mining sector still somewhat reluctant to expand investment – despite a more favourable currency and low interest rates – it seems somewhat doubtful that the government will get its wish. As a result there is an argument that they should be pursuing expansionary fiscal policy, despite the likelihood of a credit rating downgrade, in order to support employment and reduce the pressure on private sector balance sheets.

The possibility that house price growth slows in Sydney and Melbourne, which would reduce household borrowing, also poses a significant risk to any attempt at fiscal consolidation. As it stands, household debt is already viewed as a systemic risk to our financial system, to the extent that APRA was forced to intervene to reduce investor activity within this sector. The government may not get much support in their budget repair from Australian households.

As a result, I believe that budget repair will occur more slowly than currently forecast. Any attempt to return to surplus by 2020-21 will prove foolhardy and ultimately undermine economic growth and employment. Don't be surprised to see further downgrades when the 2017-18 budget is released in May.