Bogle's Folly and the relentless rules of humble arithmetic

One of my earliest investing mistakes came in the early 1990s when I walked into the offices of a financial planner (need I say more?) in Crows Nest, Sydney.

I was in my late 20s, had saved a bit of money and was after some advice. Within the hour I was the expectant owner of a Macquarie Bank product with an annual 4 per cent management fee.

A few years later I calculated my returns; they were almost exactly the same as the overall market return for the period, minus the fees I'd paid. Some might say I got off lightly but, reflecting on the pitch, I saw all the usual human frailties – hope, greed, and ego – expertly manipulated by a congenial adviser.

The decision thereafter was easily rationalised: Macquarie Bank was stuffed with smart people and I didn't want to miss out. “I don't offer this product to every client,” the adviser had said. No, ‘course not. And the 4 per cent fee? It was well worth it because my returns were going to beat everyone else's. What I didn't know was that everyone else was paying 4 per cent to beat me.

Research indicates that at least three quarters of people think they're above average drivers. In education, 94 per cent of college professors think they perform above-average work. Psychologists call this illusory superiority. The rest of us know it as the Lake Wobegon effect, a place, said Garrison Keillor, where “all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average".

The finance industry works on a similar principle. Almost every investor thinks they can beat the market, or identify someone that can. On the other side of the trade are no shortage of fund managers willing to confirm the misconception. To paraphrase Monty Python's Life of Brian, “We are all outperformers". And repeat.

It's patently untrue and demonstrably so. In 1974, John “Jack” Bogle decided to do something about it, launching the Vanguard Company. With $US5.1 trillion under management it is now the second-biggest asset manager in the world.

Born on May 8, 1929 in Verona, New Jersey, Bogle's family founded American Can but lost everything in the crash. His father hit the bottle, the marriage fell apart and Bogle got into Princeton on a scholarship rather than a wealthy parental donation. His frugality endures. Bogle has flown first class only once, when he was offered a $50 upgrade.

Source: FNlondon.com.

His central insight was radical only in the sense that it challenged the established order. His thesis, according to Barron's, “laid the intellectual groundwork for the index fund”, in which he argued that mutual funds “may make no claim to superiority over the market averages”.

Bogle believed the industry's growth would be best served by a "reduction of sales loads and management fees" and that funds should avoid creating "the expectations of miracles from management". The theory was put into practice with the 1976 launch of the First Index Investment Trust, the forerunner to the Vanguard 500 Index Fund.

At the time, the average US mutual fund was charging 2 per cent a year. Bogle expected his new fund to charge 0.5 per cent. Making a proposal to the directors in April 1976, he offered a table showing the impact of this differential on $1 million invested over 30 years.

An assumed annual return of 10 per cent would lead to a $17.5 million sum after three decades; at 8.5 per cent it would be just $11.5 million. The lower fee payoff was worth six times the original investment. Such are the relentless rules of humble arithmetic and compounding.

Many analysts think Amazon's strategy of lower prices to increase revenue is groundbreaking. Bogle got there first, a genuine disruptor, building a vast business as a result.

Wall Street wanted none of it, of course, calling the new index fund “Bogle's Folly”. As the idea gained traction, however, the putdowns turned to scaremongering. One analyst called index investing “worse than Marxism” – which, for him and his career, was possibly correct – another “un-American”.

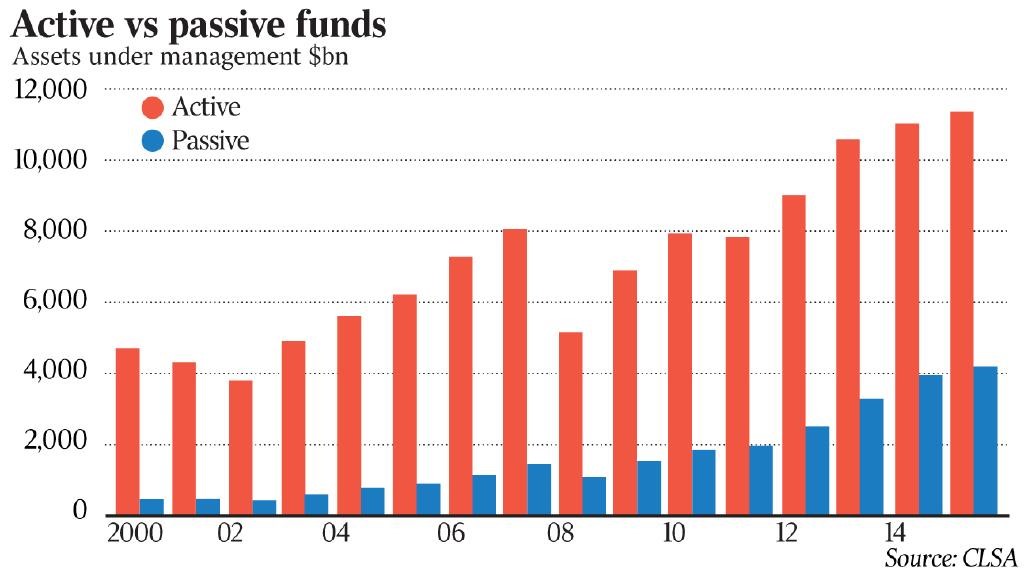

Vanguard's growth since has progressed according to Mahatma Gandhi's misattributed quote: “First they ignore you; then they laugh at you; then they fight you and then you win". Still, Bogle's victory has taken a lifetime. In Australia, passive or index funds now account for about 25 per cent of total assets under management. In the US that figure is approaching 50 per cent.

Source: CLSA, via The Australian.

For most investors, this is great news. The so-called Vanguard Effect is believed to have saved investors upwards of $US1 trillion by driving costs in the industry down and the compounding effect on returns from the money saved.

Local active funds also conform to Bogle's premise. Here's the Morningstar data to May 2018.

|

Total Funds |

Underperform Benchmark |

Outperform Benchmark |

Avg Underperformance % |

Underperforming |

|||

|

Fund # |

Avg Fees % |

Fund # |

Avg Fees % |

||||

|

1Yr |

7,928 |

5,139 |

1.64 |

2,789 |

1.49 |

(2.21) |

65% |

|

2Yr |

7,621 |

5,351 |

1.68 |

2,270 |

1.44 |

(2.19) |

70% |

|

3Yr |

7,388 |

5,790 |

1.67 |

1,598 |

1.41 |

(1.92) |

78% |

|

5Yr |

6,913 |

5,549 |

1.66 |

1,364 |

1.53 |

(2.07) |

80% |

|

10Yr |

5,312 |

4,025 |

1.73 |

1,287 |

1.47 |

(1.75) |

76% |

Source: Morningstar, via InvestSMART.

The last line in the above table might catch your eye. Over a 10-year period, three quarters of Australian active funds underperform their benchmark by 1.75 per cent. The average fee for so doing is 1.73 per cent. Coincidence? I think not.

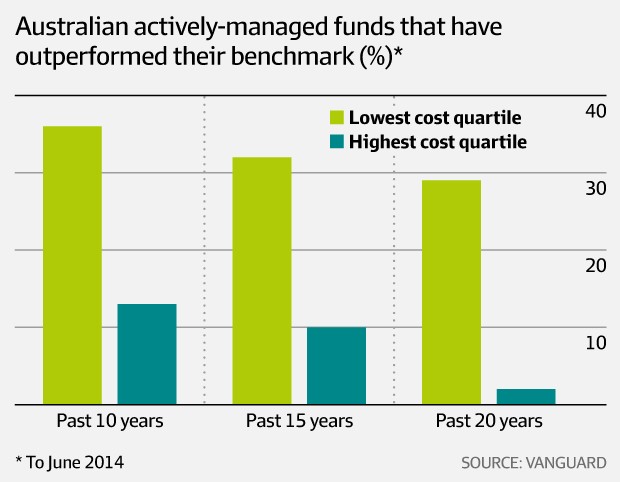

What about the 25 per cent of active managers that do manage to beat their benchmark? Even here fees play a central role. Over the very long term, the lowest-cost active managers outperform the most expensive active managers many times over.

Source: Vanguard, via AFR.com.

Is investing really this simple; just buy a low-cost index fund and get on with your life? The world's richest man, the high priest of active management no less, seems to think so. On page 20 of the 2013 annual Berkshire Hathaway letter, Warren Buffett writes of the advice he has given to the trustee of his estate:

“Put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund. (I suggest Vanguard's.) I believe the trust's long-term results from this policy will be superior to those attained by most investors – whether pension funds, institutions or individuals – who employ high-fee managers.”

All the evidence suggests he's right. So why is someone that has spent the best part of 20 years researching, practising, and preaching the virtues of value investing and its ability to beat the market telling you not to bother?

The truth is that most people aren't cut out to seek outperformance, let alone achieve it (which, I'm happy to say, we have managed to do over the life of Intelligent Investor). Unless you really enjoy it, perhaps to an obsessive degree, beating the market is a time-consuming and emotional affair. And then, after all the hassle, you might not beat the market anyway. It does not suit most people (and if it did, it would not work).

For such people, index investing is a better option, as long as you follow the simple rules helpfully laid down by John Bogle in his book Common Sense on Mutual Funds (in brief; buy low-cost index funds and hang on to them).

In a fortnight I'll return to this issue, but with a slant towards active managers, the role they perform and the characteristics of those that do manage to beat their benchmark.

Enjoy the weekend and raise a glass to Bogle's Folly, the index fund – an idea that famed economist Paul Samuelson ranks up there with the wheel, the alphabet and cheese. Big call but he might be right.