Aluminium game changer

Summary: Alcoa has traditionally mined bauxite, the ore of aluminium, then refined and smelted it. But the company is sending trial shipments of unprocessed ore overseas, and a number of other small companies also plan to start exports. |

Key take out: The price of bauxite has overtaken iron ore and is rising. Costs vary, but the lowest estimates point to a potentially handsome profit margin. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Mining stocks. |

In a development that will likely be as much trouble politically as it may be lucrative financially, Australia's aluminium industry is facing the prospect of a severe reduction in onshore manufacturing of aluminium.

With the precedents of oil refining and iron ore processing already established, there is now every chance alumina refining – a business that has kept thousands of jobs in regional Australia – could now be in jeopardy.

The rise of bauxite as a raw material export with the potential to generate fatter profits than iron ore has taken another step up with the aluminium giant Alcoa quietly sending trial shipments of unprocessed bauxite, the ore of aluminium, to overseas refineries.

Until now Alcoa has dismissed suggestions that it should cash in on growing international demand for bauxite saying it would stick to its integrated business model of mining the ore, refining it into an intermediate stage (alumina), and then smelting the alumina into aluminium metal.

Earlier this year the managing director of Alcoa in Australia, Alan Cransberg, said there were no plans to export unprocessed bauxite ore: “for the last 50 years our focus has been converting bauxite locally to alumina and that has been a very good business for us.”

What's changed, and it sends an interesting signal to a number of companies trying to enter the bauxite export business, is that unprocessed bauxite is in greater demand than either of the ore's processed stages, alumina or aluminium.

International interest in getting access to more Australian bauxite has been partly generated by an Indonesian ban on the export of unprocessed ores, including nickel and bauxite.

China in particular has been seeking additional bauxite supplies which has encouraged Australia's major exporter of the ore, Rio Tinto, to plan a big expansion of its mines near Weipa in far north Queensland.

A number of small ASX-listed companies such as Bauxite Resources, Australian Bauxite and Metro Mining also plan to start exports, along with a number of unlisted companies, such as the unlisted Gulf Alumina, which has strong Chinese backing, and includes on its board Orica's current managing director, Alberto Calderon.

News of the change in policy by Alcoa was mentioned almost in passing during a briefing of analysts in the US after the release of the parent company's second quarter profit result, though there is a close Australian connection to Alcoa through the ASX-listed business called Alumina Ltd.

Alcoa of the US and Australia's Alumina are owners of a business called Alcoa World Alumina and Chemicals (AWAC), with the US company having a 60 per cent stake in AWAC, as well as day-to-day control. Alumina Ltd has a 40 per cent stake.

The mention of trial bauxite exports by AWAC during the Alcoa briefing was noted by a handful of investment banks, including Goldman Sachs and Citi.

Both banks said the results of the trial shipments were not yet known and that the bauxite shipped overseas was from AWAC's mines in WA's Darling Range had significant differences in grade and chemical composition to the ore generally consumed by overseas alumina refineries.

Goldman Sachs said that Alcoa had confirmed: “that it had deployed samples of bauxite for testing to customers to determine its suitability and potential for bauxite exports”. Citi said the lower grade of Darling Range bauxite had “historically made it uneconomic to export” though the ore's chemical composition made it cheaper to process.

If Alcoa's trial shipments are successful, and if differences in handling low-grade WA bauxite can be overcome in the same way Asian steel mills learned how to use different types of Australian iron ore, then bauxite exports could blossom – with the unfortunate consequence being that alumina and aluminium exports might fall.

For Australia, with some of the highest energy and labour costs in the world, the bauxite export question goes to the heart of whether most forms of mineral processing will remain a viable businesses when better profits can be earned from simply digging and delivering an ore.

Like iron ore, bauxite is a relatively easy mineral to mine because it is generally found close to the surface having been formed by the erosion (over billions of year) of harder rock.

The bauxite/alumina/aluminium business is complex because of the three stages of its operation, changes in supply and demand of each product, and the differing chemical composition of bauxite ores. Some bauxite ore has close to 50 per cent alumina in content, while other ore is of a much lower grade (27 per cent to 30 per cent alumina).

Several key factors in the bauxite/alumina/aluminium equation have changed over the past few years, including:

- Australian costs, especially for energy, have risen to the point where aluminium smelting has become marginally profitable, or loss making, which is why Alcoa last year closed its Point Henry smelter near Geelong.

- China and other countries, such as Saudi Arabia, have been over-producing aluminium and alumina without ensuring reliable future supplies of bauxite.

- Supplies of bauxite have become harder to source with the most important source, the west African country of Guinea, becoming less reliable, partly because of an infrastructure shortage and also because of local health issues (it is in the Ebola infected region of Africa), and because of the Indonesian ban on the export of unprocessed ores.

- Alcoa has become a more aggressive company, seeking to slash costs (such as closing Point Henry) while looking for new sources of revenue, and

- What's happening with bauxite could turn out to be a re-run of the way Brockman iron ore (the high grade, lump or once preferred by steel mills) was overtaken by Marra Mamba (lower grade ore) as major blast furnace feed, once steel mills learned how to manage the different chemistry of the ores.

Changes to the bauxite business were first flagged in Eureka Report last year (Bauxite's blistering pace, May 30, 2014).

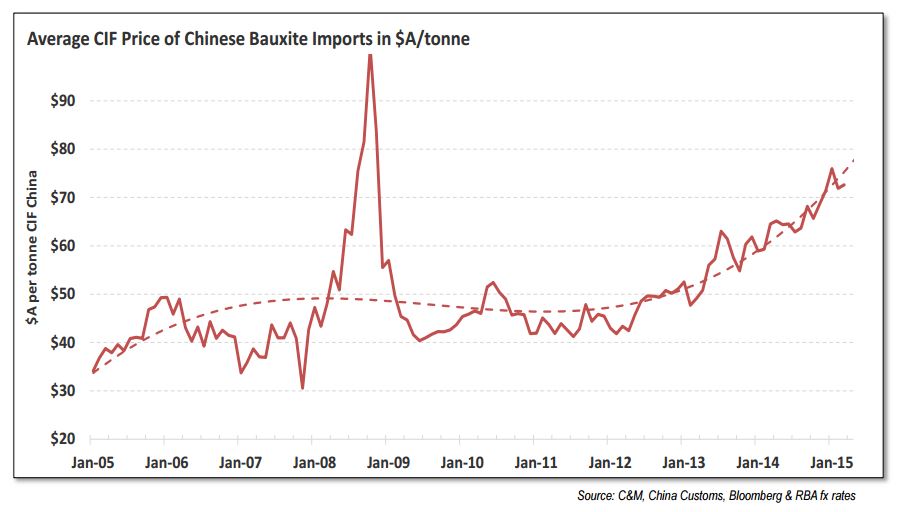

Back then, iron ore was selling for around $US97 a tonne, having fallen from $US135/t at the start of 2014. Bauxite was selling for around $US65/t having risen from $US50/t.

Today, iron ore is selling for around $US50/t, with the occasional dip below that critical price. Bauxite has continued to rise and is now selling for around $US70/t.

What was suggested in May last year, that bauxite could overtake iron ore, has occurred.

The price of a raw material is one thing. The profit margin is another, and far more important, as investors in some struggling iron ore miners are discovering.

The bauxite mining cost structure equation is similar to iron ore in that it is a bulk commodity with around 70% of costs associated with infrastructure and materials handling. The actual mining cost is of less importance than the transport economics.

Costs vary from project to project. For Bauxite Resources, the top and bottom of its cost estimates are $US70/t (around the current price for bauxite), and $US20/t, with the lower estimate pointing to a potentially handsome profit margin.

It is rising demand and a rising price which sets bauxite apart from iron ore today.

Another difference, and this is when political factors might come into play, is that much of Australia's bauxite has traditionally been upgraded into an intermediate product (alumina) or a metal (aluminium). Most attempts to upgrade iron ore for export have failed.

If Alcoa joins Rio Tinto as a successful exporter of bauxite then another Australian mining industry could become a simple dig and deliver operation, bypassing the value-added (and job creating) stages of processing.

The closure of Point Henry was a warning shot across the bows of the alumina/aluminium processing industry, particularly for the ageing Kwinana alumina refinery in WA which was built largely to supply Point Henry with alumina.

AWAC operates three refineries in WA with Pinjarra and Wagerup, the BHP Billiton spin-off South32, operates the fourth at Worsley.

The prospect of Darling Range bauxite being exported in commercial quantities will be ringing alarm bells at all of the refinery operators, especially if the profit margin on ore significantly exceeds the profit margin of alumina.