Alpha impaled by infinite monkey

Between June 2001 and 2017, Intelligent Investor made 510 buy recommendations, delivering an annual average return of 14.1 per cent. The cumulative outperformance over the total return of the ASX200 over the same period was 105 per cent.

To quote a certain prime minister comfortable blowing his own trumpet, “this is a beautiful set of numbers”. It is also misleading. As I wrote in Bogle's Folly and the relentless rules of humble arithmetic, only a small fraction of active managers beat their respective benchmark; the rest underperform it by their fees or thereabouts.

Active managers typically promise an above-average return whilst delivering a worse than average result. Most investors should therefore pick a low cost index fund, correct for our local market's over-representation of banks and resources, pull in some international index funds and get on with their lives.

Or they could invest with us and do much better. Well, maybe. Tempting as it is to profess skill and expertise, an awkward possibility lies behind our impressive 17-year track record; there's a small possibility we just got lucky.

The infinite monkey theorem stipulates that an immortal monkey and a typewriter would eventually produce the works of Shakespeare. Investment returns aren't quite that, but they're more random than we realise.

Caption: An active fund manager reviews his portfolio

A month-long performance art installation at Paignton Zoo in Devon, England, involving six macaque monkeys and a typewriter, delivered an uninspiring five pages of type dominated by the letter “S” and various unhygienic outputs. The lead male got off to a great start by taking a stone to the keyboard while his fellow budding authors urinated and defecated on it.

This is not a metaphor for what might happen to your super if you leave it with an active manager. Most can, in fact, spell the word “banana”. But it does illustrate how chance plays a bigger role in success than we think.

Let's go through the numbers. Imagine you invest $100 in a fund with only two possible outcomes in any given year, both of which are equally likely; your investment will either increase by 20 per cent or it will fall by 25 per cent. (A loss of 20 per cent is comparable with a gain of 25 per cent in the same way that doubling (a gain of 100 per cent) is comparable with halving (a loss of 50 per cent).)

As the decades pass, the gains and losses offset each other. But over 10 years a broad range of outcomes exist. If 10,000 investors each stumped up $100 on the same basis and held on for a decade, this is how one might expect the distribution to look:

|

Group |

Wins |

Losses |

Value of Investment ($) |

Per cent of outcomes |

|

A |

10 |

0 |

$931.32 |

0.10% |

|

B |

9 |

1 |

$596.05 |

0.98% |

|

C |

8 |

2 |

$381.47 |

4.39% |

|

D |

7 |

3 |

$244.14 |

11.72% |

|

E |

6 |

4 |

$156.25 |

20.51% |

|

F |

5 |

5 |

$100.00 |

24.61% |

|

G |

4 |

6 |

$64.00 |

20.51% |

|

H |

3 |

7 |

$40.96 |

11.72% |

|

J |

2 |

8 |

$26.21 |

4.39% |

|

K |

1 |

9 |

$16.78 |

0.98% |

|

L |

0 |

10 |

$10.74 |

0.10% |

If you were unaware of the underlying rules and needed someone to manage your money, who would you choose? I'm guessing a Group A manager. But even if you know the random nature of the results, I think most of us would make the same choice because if you can't select for skill, choose luck. Such are the mechanics of the human brain, seeking meaning in meaninglessness.

The misunderstanding has real consequences, even for self-deluded participants. Those 10 investors in Group A, for example, might band together and form a hedge fund, or an investment publication, trading on their “outstanding” track record (see Buffett's essay The superinvestors of Graham and Doddsville for more).

Over time, the variance reduces and the bell curve narrows. But over a decade - considered long term in investing - the effects of randomness are easily mistaken for skill. What this means for Intelligent Investor's 17-year track record I could not say. Maybe ask me again in a decade.

In Luck Versus Skill in the Cross Section of Mutual Fund Returns, Eugene Fama of the University of Chicago and Ken French of Dartmouth College examined the returns of 3,278 US mutual funds from 1984 to 2006, trying to establish what managers outperformed - alpha in the parlance of the industry - above the level of chance. This is what they concluded:

“...for the vast majority of funds true alpha is negative. And even for the top percentiles of [managers], strong past performance is probably due to chance. Going forward, the estimates of true alpha for the top performers is close to zero - about the same as for an efficiently managed portfolio of passive funds.”

If this hasn't put you off active investing - and I wouldn't blame you if it has - what factors should you look for in an active manager? What characteristics increase your chances of finding one with skill rather than a generous helping of Lady Luck?

Firstly, and counterintuitively, track record does matter. Our 17-year history could be explained by luck, but there's only a small chance of it, as the table above illustrates. As the years pass and the outperformance (hopefully) continues, that probability diminishes further.

The converse is also true. One, three and five year track records are meaningless. The shorter the timeframe the greater the likelihood of luck explaining alpha. Says research director James Carlisle, “even investors with good 10-year track records are likely to lose to index trackers over the next 10 years”.

Track record is a useful guide to skill when registered in decades, by which time it's probably too late to be of any use. Great.

The second characteristic, again counterintuitively, is proposed by the aforementioned Eugene Fama, of efficient market hypothesis fame. Fama and French's three factor model, a progression on the capital asset pricing model, suggests that small capitalisation stocks and value-based stocks have a higher propensity to outperform.

For value investors, always looking to affirm their rectitude, this makes sense. When I asked Graham Witcomb his thoughts on fund managers more likely to outperform, he recommended looking for managers with “concentrated, weird positions. If they hold 50 stocks, I'd say no immediately. Ten to 20, and the more esoteric the better. No BHPs and banks etc”.

If you're paying a manager to beat the index they must be willing to take risks and do something different to the market. If they aren't doing that, they are the market and your returns will be the market minus fees. (To see how your funds are going on fees and performance, try our new tool, Compare Your Fund.)

The investor, meanwhile, needs to be willing to accept the extra volatility such an approach entails. The InvestSMART Australian Small Companies Fund for example, managed by our own Alex Hughes, got off to a flyer, returning 9.2 per cent in its first quarter compared with the ASX Small Ordinaries index return of 4.4 per cent. first three months. A year on from launch it was 8.4 per cent behind the benchmark index. That's what happens when you take weird and wonderful positions.

Value investing is, in my view, the purest expression of this mindset. The fact that the person most responsible for making the case against active management seems to support it is encouraging.

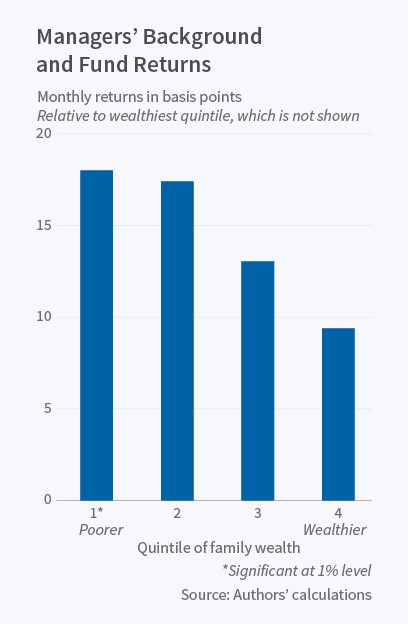

What else? A fascinating research paper suggests that fund managers that do beat the market tend not to come from privileged backgrounds. “Managers born poor are promoted only if they outperform,” says the researchers, “while those born rich are more likely to be promoted for reasons unrelated to performance.”

Of course, that couldn't happen in Australia's classless society but here's the key chart, via Timothy Taylor's Conversable Economist blog, anyway:

Source: Family Descent as a Signal of Managerial Quality: Evidence from Mutual Funds (August 2016, NBER Working Paper No. 22517).

Taylor puts it like this: “When those who face higher barriers to success manage to overcome those barriers in any occupation, it may often be a sign that their competence level is not just high, but exceptionally high.” So, choose successful battlers over seemingly successful silver-spooners.

The third and fourth factors - average holding periods and inside ownership - have a more practical bent. According to a US paper by Cremers and Pareek (Patient Capital Outperformance: The Investment Skill of High Active Share Managers Who Trade Infrequently), value managers with longer holding periods tend to outperform.

It can take years before the market accurately prices an undervalued stock. Average holding periods are therefore an indicator of conviction. Such managers might be wrong, but they're prepared to wait to find out. Those with shorter holding periods are probably less confident in their reasoning or merely impatient. Neither are good.

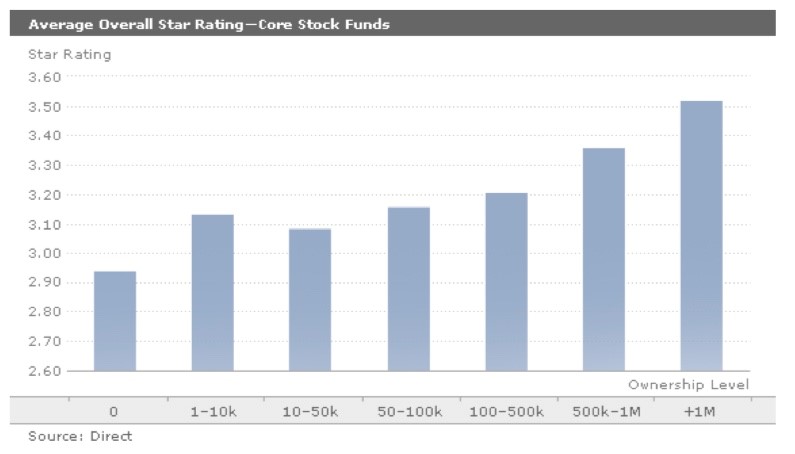

To our last factor, inside ownership. Fund managers investing in their own funds is another sign of conviction, one with real money behind it. In 2011, Morningstar found that funds with a higher level of inside ownership earned a higher star rating.

Source: Morningstar via Shore Funds

I'm not a great fan of ratings systems like this but I do believe that good managers should enjoy the taste of their own cooking. If they're not investing in their own funds why should you?

These pointers won't guarantee you'll find an active manager that will beat the market, but they should reduce the risk of landing on an infinite monkey.

I'm away for the next two weeks and leave you in the capable hands of Eureka Report editor Tony Kaye.

Enjoy the weekend.

Note: Changes were made to this article at 9.30am on Saturday 7 July, particularly in regards to the table, as the original copy referenced an earlier rather than final draft.