A time to be sensible

Welcome to the first Weekend Brief of 2018. Sadly, the year has began like an ADHD version of the one just passed, featuring an obsessive focus on anything remotely to do with bitcoin, closely followed by Trump and his itchy, nukey, finger.

Before getting to the meat of the matter, let's dispense with what Nassim Taleb might call the long-tail risks. That cryptocurrencies are a bubble is as plain as can be. Intelligent Investor analyst Graham Witcomb surely delivered the best headline of the crypto era when he wrote The worst way to make a 100,000 per cent return. The more salient concern is whether the bursting of this bubble might impact the wider economy.

That's unlikely in my view. As the GFC proved, one needs to worry only when the banks roll up their sleeves in search of ignorant investors and a quick buck. There's little evidence of that thus far. There are no margin loans for bitcoin, no NINJA-style mortgages for ethereum, at least not from the mainstream banks.

This looks like one bubble that can burst without too many broader ramifications. Unless the kids are using your credit card to punt on Useless Coin (“The world's first 100 per cent honest ethereum ICO. No value, no security, and no product. Just me, spending your money”), it's not worth worrying about.

Much the same goes for the prospect of a nuclear war. Last year the S&P 500 rose 21.8 per cent, presumably in anticipation of new tax laws, not a nuclear strike. The latter risk was quickly and sensibly shoved aside by the market, if not the media, who, unlike investors, are still intent on taking what comes out of Trump's mouth seriously.

Both themes illustrate how the media mainlines stories that play directly into our fear and greed, distorting our assessment of risk, a psychological bias much discussed in Thinking, Fast and Slow. The effect is to get us to obsess over unlikely threats at the expense of the main game – a dispassionate calculation of real risk.

Recently, Gaurav Sodhi made the case that we might be approaching the end of a remarkable bull run (see Enter the bull market). I'm going to look at the same issue in another way, by asking three questions: Are stocks expensive? If so, can higher prices be justified? And, if not, does this mean we're headed for a crash?

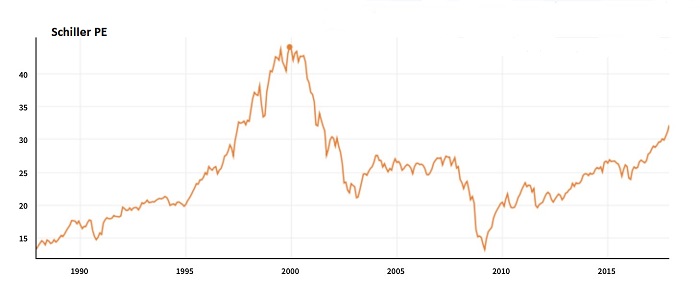

To the first question. The chart below shows the Schiller PE (also known as the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings or CAPE ratio) for the last 30-odd years. The metric is useful because it's based on average inflation-adjusted earnings from the previous 10 years of all S&P 500 stocks.

During the dotcom boom the CAPE ratio hit 44. Let the record show the long-term average since 1881 has been 16. So, yes, stocks were expensive then, especially crappy ones.

At the low point of the GFC the ratio fell to 13, not as cheap as one might expect due to the impact of 10-year averaging. As of December, the S&P 500 CAPE ratio stood at 32. Right now, one of Australia's better businesses, Carsales, is on a forecast PER of 26. By any historical measure, US stocks at least are expensive.

Figures for Australia are harder to find and country-to-country comparisons have their problems. But according to Siblis Research, our CAPE ratio is about 16, higher than the local average but not dramatically so. Still, there's no doubt cheap stocks are becoming harder to find, which is why there are only eight stocks on our Buy List. The rise in the local market over the past few years has much to do with it.

If stocks are expensive now, can they go higher? Of course. We know this to be true, because that's what happened last year and the year before that. In fact, a Google search for “bull market about to end” for this month and January 2017 offers the impression the bears simply republished the previous year's article.

Here's a summary of their case: Quantitative easing, which has pushed interest rates to record lows, boosting share prices, is coming to an end. “Unconventional monetary policy”, as the wonks call it, is about to go conventional. That means higher rates, and potentially higher inflation. Asset prices are already rich and, with global growth rebounding, labour markets tight and rates rising, a recession is imminent.

Most bull markets end when investors anticipate a recession. They tend not to wait for the numbers to come in. If this bull run continues until the end of August, it will be the longest in US market history. And the performance of stocks has beaten bonds in seven consecutive years, the longest since the 1929 crash. In other words, say the bears, we're due.

The bull case is equally straightforward. For the first time in a decade the world's major economic powers are enjoying substantial economic growth. Even Japan, despite a rapidly declining population, is growing. And the US, China and Europe are cracking along – well, compared to the last decade anyway. As outgoing US Fed Chair Janet Yellen said recently: “The economic expansion is increasingly broad-based across sectors as well as across much of the global economy.”

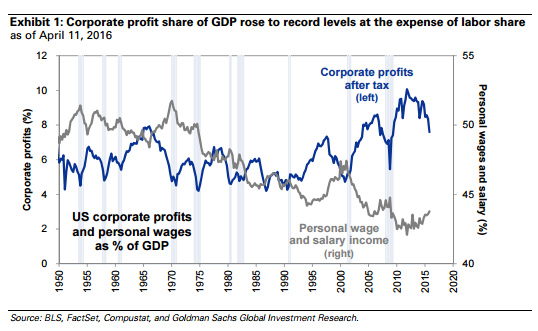

There's also very few signs that inflation is about to break out, which means that whilst interest rates may still rise, they won't do so by much. Wages growth is static or declining (which is a problem of a different sort) and corporate profits are buoyant. McKinsey estimates that between 1980 and 2013, global corporate profits as a percentage of GDP rose 30 per cent.

That means more dividends and share buybacks to support share prices, even without the hundreds of billions in US dollars that will be repatriated by the likes of Apple, Google and Amazon.

What about Australia? We haven't experienced a recession in 26 years, which should strengthen the “we're due” argument. And yet, last year was the first in which employment increased every single month. There is no sign of a slowdown in Chinese demand for commodities, and whilst the unemployment rate has increased recently, this was due to a higher participation rate. Even November retail sales were stronger than expected.

Given these circumstances, does the bull argument imply that higher share prices are justified? Possibly.

You see, the world has never seen anything like the last decade. The desire to drive down interest rates to levels once thought impossible is a policy that until 2009 had never been tried. It saved the world from a depression, but it may have also had a permanent impact on what people think are reasonable multiples for stocks. I rarely buy into the “this time is different” narrative, but these unusual circumstances mean a bull market could run a lot longer than we had previously thought.

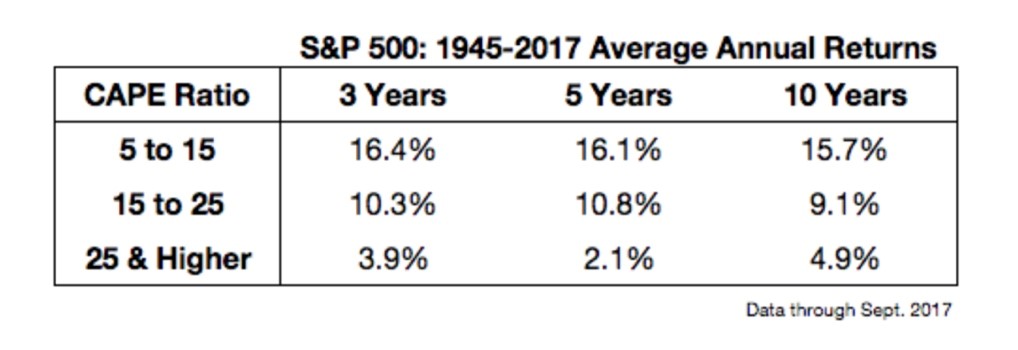

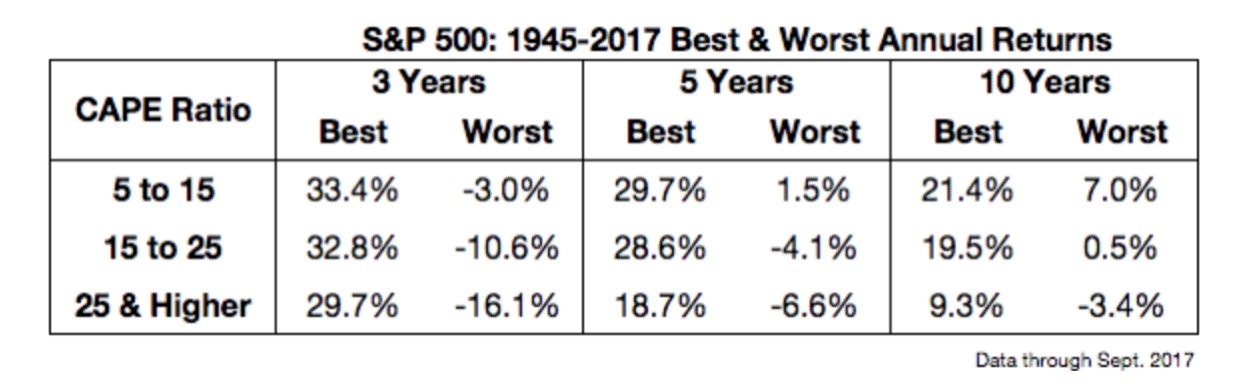

To the final question. Do higher share prices indicate a crash? The answer is a distinct “no” according to Ben Carlson, who blogs at A Wealth of Common Sense and writes for Bloomberg. Here's his data:

The first table shows that higher-than-average stock market returns do occur from lower valuation starting points, and vice versa. Buy cheaply and you're more likely to get a higher return. The second table, showing the range of best and worst annual returns from the same CAPE ratio bands, reveals how deceiving averages can be. You can pay CAPE multiples of 25 or more and still get an almost 30 per cent return over three years.

The data does support the view that the best returns over the long term are secured by those that buy cheaply, but as a timing tool stock valuations are useless. Just because stock prices are high does not mean they cannot go higher.

Such an environment offers its own challenges. There is nothing more galling than a newly-minted bitcoin millionaire with zero understanding of the risks they've taken to get there. Gaurav's advice is pertinent: “This is a time to prepare for fools boasting of fortunes and the complacent complaining about caution. As we enter a bull market unrestrained, this is the time to resolve to act sensibly.”

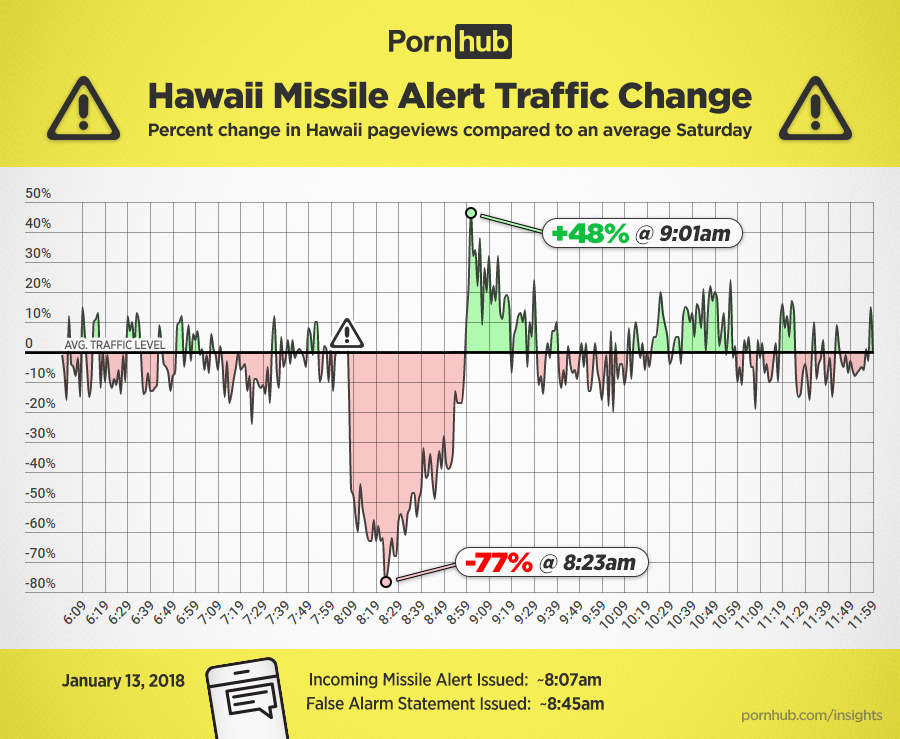

Finally, to the last chart of the week, one that suggests some people really struggle with acting sensibly.

Early on the morning of January 13, a missile alert was (falsely) issued in Hawaii. This is what happened to visitor traffic on popular internet site PornHub:

Within 10 minutes of the alert website traffic had fallen 77 per cent. Makes you wonder what the remaining 23 per cent were doing though, doesn't it? Bitcoin speculators taking a quick break is my guess.

Have a good weekend.