A bonds Plan B if franking credits are axed

Summary: Many income reliant investors will be challenged if franking credits are abolished.

Key take-out: Certain fixed income products will become more attractive as a result.

Labor's stated policy of removing dividend franking credit refunds, if it's elected, will make some shares and hybrids (because of their equity structures) less attractive to investors.

Some shares would lose their shine, but I'd expect investors to largely keep holding them, with bank dividends of around 5-6 per cent per annum still deemed ‘attractive enough'.

It's worth reinforcing that bank share prices and capital aren't guaranteed. Commonwealth Bank's 5.75 per cent dividend looks appealing, but had you invested a year ago, its share price is down circa 8 per cent. Even if you are able to claim franking credits with a combined income of roughly 8 per cent, you would be clinging to a break-even position.

Too many investors discount movements in share price for prized dividend income, even though dividends can be cut or not paid at all. Whether you are investing for income or growth, bank shares are a gamble. Subordinated bonds – issued by many Australian financial institutions – are better for income investors. I'll circle back to them in a moment.

Complex hybrids have been long-term favourites of investors seeking income. But a loss of franking credits, especially in this low interest rate environment, would take away any premium over lower-risk subordinated bonds, which would then become superior investments.

For example, the ANZPF has its first call in 2023, roughly equating to a five-year term. It has a yield including franking of 5.71 per cent per annum, but without franking the annual return falls to about 4 per cent per annum.

All the major bank securities trade in a tight range, so a Westpac subordinated bond of similar term pays 4.1 per cent per annum, but is only available in $500,000 parcels. Bank of Queensland also has a subordinated bond over a similar length, with a yield to expected maturity of 3.86 per cent, which requires a lower minimum investment.

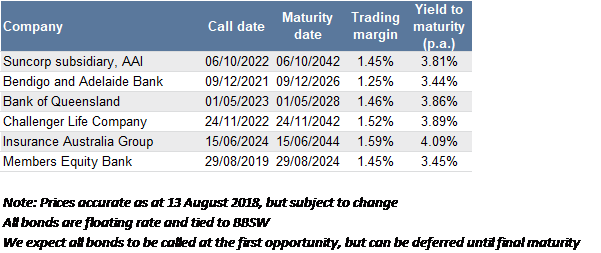

A simple ‘Plan B' could be to invest in the subordinated bonds from similar, if not the same, institutions. See sample financial institution subordinated bonds below that include a range of call dates. Note the bonds do not have to be held until maturity. They can be traded on a T 2 business day basis.

Sample financial institution subordinated bonds

How do subordinated bonds and hybrids differ?

Risk increases at each stage as you move down the capital structure: starting with deposits, then senior unsecured bonds, subordinated bonds, hybrids, and finally to the highest risk investment – shares.

Compressed interest rates make differentials between the investments smaller in the capital structure stack compared to historical averages.

Risks are present in any investment. Both the subordinated bond and the hybrid have call dates: typically after five years for the bond, but the range for the hybrid could be up to eight years. However, the bond has a final maturity date – usually at 10 years – whereas the hybrid has conditional conversion dates subject to APRA approval.

Failure to meet the conversion conditions means the hybrid becomes perpetual, and investors must decide to sell at market rates to recoup capital.

The bond is issued at $100, and investors expect $100 to be returned at maturity. While bond prices move over the life of the bond, the return of face value at maturity helps preserve capital.

Income is specified for both investments. However, income on the bond must be paid, otherwise it is a ‘default event'. The hybrid is designed to be loss absorbing and protective of the bank's survival, so income can be forgone and never has to be paid.

There is a dividend stopper clause – which somewhat protects hybrid investors – but the risk of losing income remains.

Income on the hybrid can also be scaled down if minimum capital levels are breached, with a floor of 8 per cent. Should capital fall below 5.125 per cent, the hybrid automatically converts to highest-risk shares. No such clause exists for the bond.

In the worst-case scenario, APRA can deem the institution ‘non-viable' where both investments convert to shares.

So, on a risk versus reward assessment, the hybrid return would be insufficient for investors if franking credits cannot be claimed.

If the ALP came to power and was able to get legislation passed to eliminate franking credit tax refunds (which would be a long process), my suggestion would be to consider other options – one of which could be a direct investment in subordinated bank bonds.