5 from 15 - Roc(s) in our heads?

Until I met John Doran, former chief executive of Roc Oil, I didn't know what it meant to fall in love with a stock. Along with many other analysts at Intelligent Investor, I took the plunge in June 2003, following the advice of our first review (Buy – $1.13). The first few lines summed up the argument: ‘Being a small oil and gas company isn't for everyone. But for those willing to take on some risk, we think the stock represents excellent value.'

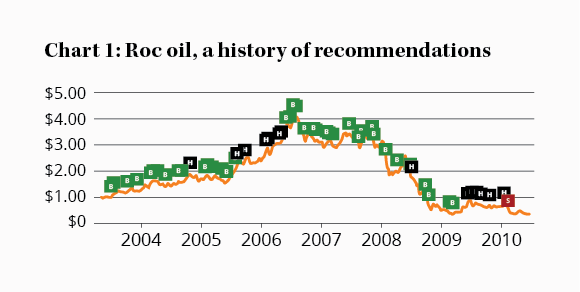

At first, that synopsis was borne out. By July 2006, Roc had risen well above $4, at which point, despite a few Holds on the way up, we doubled down. The company had acquired a stake in a block off the coast of China at what appeared to be a cheap price and all looked good.

History shows that it wasn't, although not due to this acquisition. The Buy recommendation of mid-2006 proved to be the top and we rode the slide all the way down, making 18 further Buy recommendations between July 2006 and March 2009. Eventually, we sold out at a price of $0.45 on 4 Feb 10. From beginning to end we lost members 60% of their stake, but far worse had you followed our advice at the top.

Key Points

-

Most investing errors are psychological

-

Beware the charms of a humble CEO

-

Always learn from your mistakes

This isn't the biggest loss in Intelligent Investor history, as the fourth article in this series, to be published later this month, will show. But Roc was perhaps the most valuable loss, leading to a raft of changes in the way we researched companies and how we made decisions. In the manner of a long-standing relationship creaking before the final break, Roc Oil was a failure that strengthened rather than broke us. Before recounting the lessons, let's push the metaphor over the edge and describe the initial spark of attraction.

In 1992, John Doran, a geologist by training and an ‘oil man' by choice, with a devoted focus on shareholder returns, took over Command Petroleum. Although the company's shares were trading at around 30 cents three years' later, Doran had created a much-improved business. Within a year, Cairn Energy recognised that value, taking the company over at $1.40 per share.

After creating a five-bagger for shareholders, Doran founded Roc Oil in late 1996, embarking on what we hoped would be a similar journey. Senior management took 15% of the stock, ensuring the focus was on long-term returns rather than massaging public perceptions. So, good CEO, owner managers, shareholder focus: tick, tick and tick.

Combining production assets with exploration potential, Roc also sported a margin of safety. The UK gas business was exceptional, operating at 75% margins whilst adding to net reserves. We valued this business at $100m plus. The company also had net cash of $45m and a raft of exploration assets in Australia, Equatorial Guinea, Angola, Mauritania and China. With a market capitalisation of $122m, these assets came free. Only one of them would need to pay off for Roc to be worth many multiples of its then share price.

Our excitement made its way onto the page. Said the first review, this is ‘a great opportunity to BUY a quality stock with the potential for huge capital gains. But please, don't expect a quick rise in price just because we have recommended it. This stock will require some patience but we're confident that patience will be handsomely rewarded.'

We were patient alright but the rewards weren't handsome. The mistake was ours and we had to own it. So, dear reader, take a deep breath and join us on the couch (former Roc shareholders will find the tissues to their left). This is how we got it wrong:

1. We lacked expertise

Tom Elder, our then resources analyst, left us suddenly to move overseas, leaving Gareth Brown, an industrials analyst, to fill the hole. At the time of Tom's departure we could have sold out and ceased coverage but we didn't. Along with members, our analytical team was invested in Roc Oil and excited by the opportunity. That probably caused us to psychologically set aside our lack of expertise.

It wasn't until the arrival of Gaurav Sodhi, a dedicated resources analyst, in 2010, that we set things straight. Gaurav got us out of the stock soon after his arrival, explaining that he was ‘struck by the absence of industry specific valuation measures like Enterprise Value/Barrels of Oil Equivalent or EV/2p'. He thought we were valuing Roc as an industrial stock rather than an oil business. Had we embarked on the journey with that mindset, Roc Oil would probably have been a Speculative rather than outright Buy.

2. Commitment bias took over

Commitment bias soon took over. This is the tendency to be consistent with previously expressed opinions or views, especially if those views are made public. Our views were public and regularly reinforced. Between June 2003 and March 2009 we issued a total of 44 Buy recommendations on Roc Oil, an average of more than seven a year. With each recommendation, we added to our bias.

3. Confirmation bias added to the problem

Initially, things went well, too well. In the three years after our initial recommendation Roc Oil's share price almost tripled. That had the effect of vindicating our initial view (even now there's an argument Gareth's research to that point was sound). But the price rise made us overconfident, allowing us to overlook the speculative nature of the business and our unconventional approach to valuing it.

4. We spotted a giant red flag and ignored it

Despite these faults we might still have made money were it not for one fateful decision. In June 2008, Roc announced it was acquiring Anzon Australia and its 53% shareholder, UK-listed Anzon Energy. Gareth recalls the press release announcing the deal and the meeting with John Doran to discuss it. ‘From the start I thought this a dumb deal, done for all the wrong reasons. John did his best to convince us the acquisition was his idea but none of us believed it. It looked like it was forced on him by a board worried about the dusters from their drilling in Angola.'

Gareth's scathing and insightful review from that period (Don't spoil our Roc Oil!) got everything right except the recommendation. Instead of selling out we downgraded to Hold at a price of $1.73. This was the fateful error, the real cause of the loss, which, in addition to confirmation and commitment bias, had two further sources.

5. We fell in love with a CEO

John Doran wasn't given to dramatic overstatement and lilly-gilding. Born in Llanelli, Wales and educated in Sheffield, England, he was a salt-of-the-earth type, with liberal doses of intelligence, humility and wit (sadly, he passed away suddenly in 2008). When we met to discuss the Anzon deal, we were susceptible to his charms. Had he been a puffed-up blowhard, it would have been easier to walk away. But he wasn't, and so we hung on.

6. We suffered from groupthink

A research company can do many things to reduce the impact of a series of mounting biases playing into a recommendation. Unfortunately, in July 2008, we weren't doing enough of them. Each analyst would make their own call on a stock and, although they might seek input from others, were not required to do so. Gareth was out on his own, bearing the weight of expectation of staff and members.

Moreover, by this stage his investment in the company was underwater, a potential source of loss aversion bias (if you've thought you'll just hang onto a stock until it gets back to the price you paid for it, that's it). Gareth was surrounded by other analysts, many of whom had also met Doran and owned Roc shares but couldn't claim any real expertise. In this way, any dissenting opinions were self-censored out of the discussion. We became a victim of groupthink.

The rest, as they say, is history. In five short years the Anzon deal managed to turn $600m into $1m, proving Gareth's instincts right. Gaurav cleaned up the mess and we made some important changes to our internal processes – Dragon's Dens in particular – that have since served the business well, proving that it's one thing to make a mistake but a far bigger error not to learn from it.